All together now: did human joiners outcompete rugged Neanderthal individualists?

When dumb cooperation trumps smart self-reliance

Imagine a simulation: take two roughly equivalent bands of brainy apex primates. Endow one with hugely powerful brains and immense creativity, individuality and self-reliance. Give the other slightly smaller cranial capacity and significantly dampen its aggregate inventiveness and individuality. But then at some point in the simulation, grant this band alone an abiding compulsion to socialize and to imitate one another. Leave the two bands in a vast closed environment and come check on them again, say 500,000 years later. One will have, by any measure, thrived and been immensely fruitful. The other will have disappeared; none of its number will have been seen in the simulation for most of the last 10% of its runtime.

This simulation could be the recent history of hominids on our planet. The also-rans we once shared it with are the Neanderthals. They had the bigger brains and their skillfully crafted artifacts show an immense creativity and individuality compared to those of our ancestors’. But we had our drives to socialize and assimilate and our compulsions to imitate and mimic, to homogenize and standardize. We became distinguished by our ever more mass societies and our hyper-efficiency where they were distinguished by their isolation and their hyper-creativity. And today, it falls to us alone to excavate our twinned storylines, one cut short tens of millennia ago, the other rolling on 8-billion strong, its innate drives to network, to copy and to join now enabled on an instantaneous, global scale.

* * * * *

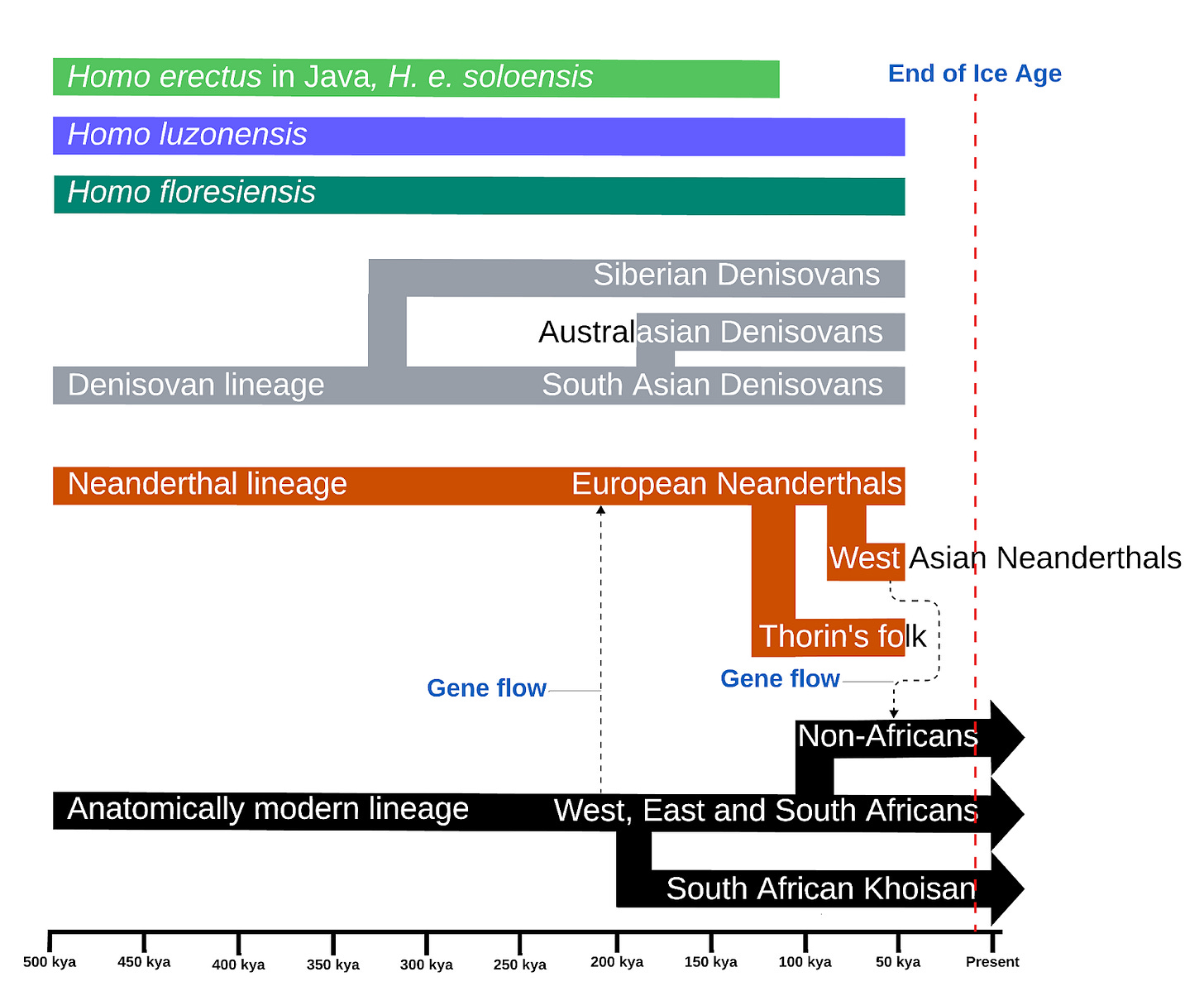

40,000 years ago, our planet’s last Neanderthals disappeared. Populations in Iberia and France that had held on in the face of anatomically modern human encroachment for 10,000 years finally succumbed, vanishing from the archaeological record. This ended a half-million-year tenure of dominance across fully three-quarters of northern Eurasia; though the earliest classical Neanderthal skulls date to 250,000 years ago, the genetic evidence tells us their ancestors parted ways with ours in Africa over 500,000 years ago.

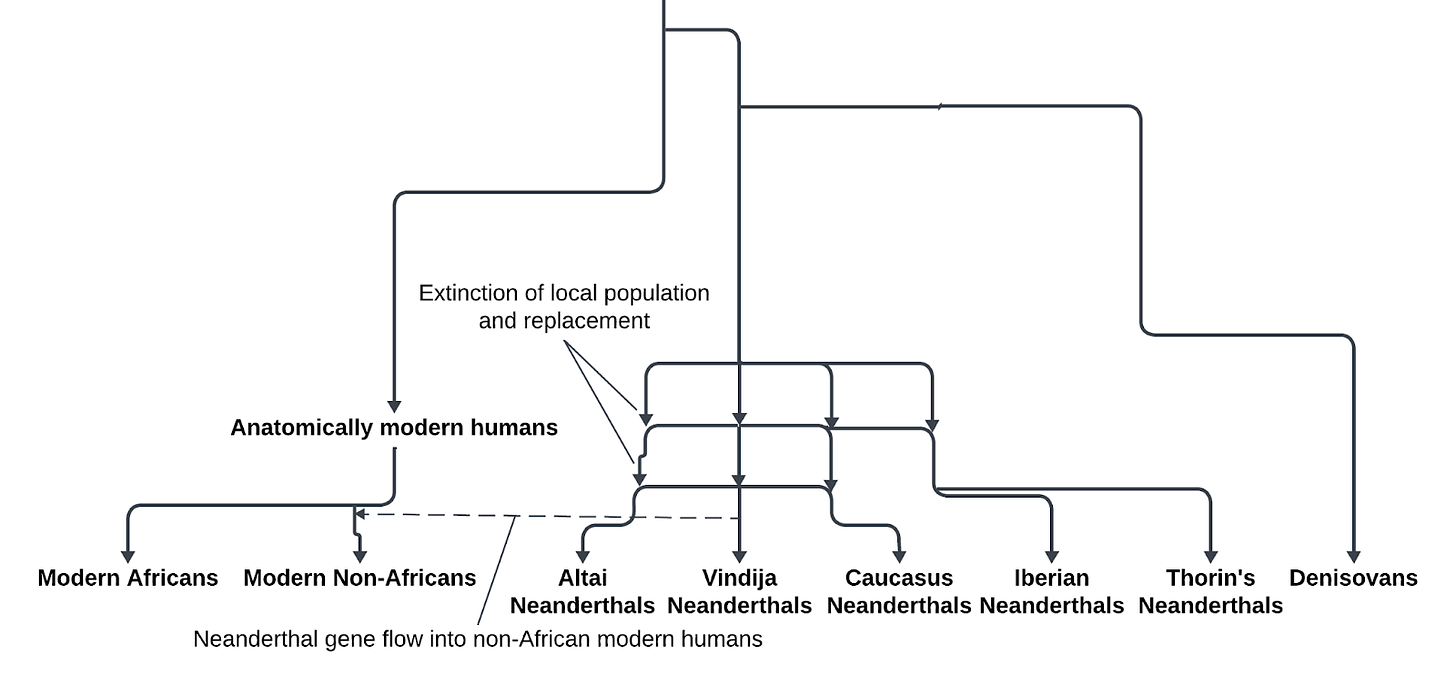

The Neanderthals’ final disappearance in northwestern Eurasia paralleled their Denisovan cousins’ demise in eastern Eurasia. Researchers have yet to positively identify Denisovan remains in East Asia's spotty and unorganized fossil record, despite recognition of their existence since 2010 when one was first sequenced from material in a Siberian cave. But odds run high that their physical remains are also already in a museum or academic cache, given that the genetics unequivocally find Denisovans to have been widespread, as attested by their having mixed with South, Southeast and East Asians in independent instances. So we know that some time before 500,000 years ago, a group of African Homo must have migrated northeast into Eurasia, and there split into two successor parties, Neanderthals who would carry on into parts north and west, and Denisovans who trekked on east, between them dominating every habitable reach of the known world outside the mother continent for hundreds of thousands of years.

But this wasn’t even all the world’s human diversity on the eve of Neanderthal extinction. On Asia’s southeast edge, paleoanthropologists find remains and tools from the diminutive Hobbits of Flores island up until some 50,000 years ago. Out on the Pacific’s western edge, in the Philippines’ northern Luzon, another small human species, Homo luzonensis, also seems to have flourished until 50,000 years ago. The discovery of these two dwarf human populations tantalizes with the growing likelihood of future discoveries still to come in the islands of Indonesia. When you add in Denisovans, this region of the world was one of the most speciose for hominins for hundreds of thousands of years (the last populations of Homo erectus in Java seem to have gone extinct only 120,000 years ago).

And then all of this changed within the space of 10,000 years, leaving our own species as what paleoanthropologist Chris Stringer calls the “lone survivors.” Our African lineage’s antecedents emerge first in the fossil record in Morocco 300,000 years ago, at the Jebel Irhoud site. But the earliest skull clearly from a modern human with no residual archaic features only appears at Ethiopia’s Omo Kibish site 233,000 years ago. Until recently, these anatomically modern humans, with gracile builds and high vaulted skulls, were thought to have only left Africa some 50,000 years ago, expanding rapidly, along the way outcompeting and extirpating all other human lineages, writing Neanderthals, Denisovans and the Hobbits out of the human story. But today we know this cannot be correct; genetic and fossil evidence for modern African-like humans in Europe and Asia appears well before the last great push outward. More than 210,000 years ago, populations with skulls more like prehistoric Africans’ than Neanderthals’ were living in and around southern Greece’s Apidima Cave. What’s more, around this time, Neanderthals also mixed with humans related to anatomically modern Africans, resulting in a telltale replacement of their original Y and mtDNA lineages.

About a generation ago, before these more nuanced realities had been fully outlined, the simplistic caricature of a single African lineage replacing all our cousins in one fell swoop 50,000 years ago had a lock on our imaginations. There were always dissenters, and many unaccounted for facts that stubbornly refused to fit the tidy account. But the narrative was strong enough to embolden Stanford paleoanthropologist Richard Klein to argue in his well-received 2002 book The Dawn of Human Culture that a macromutation 50,000 years ago first granted a single African population the ability to speak articulately, thus clearing the field of all human also-rans in just 10,000 years by dint of a newfound cultural flexibility. Over twenty years later, the combination of a richer fossil record and paleogenomics’ explosive growth has wholly undermined Klein’s posited mechanism. The expansion Klein described turns out to have been only of Eurasians and Australians; Africa itself was not initially affected. It was not even the first of the “out of Africa” expansions, in fact, it was the last of many.

But that still leaves us with the question: what happened 50,000 years ago? The Dawn of Human Culture described a real phenomenon, even if Klein’s posited biological and genetic cause doesn’t fit the facts as we know them today. In a recent interview, Harvard geneticist David Reich hazarded a hypothesis that a cultural innovation, unconditioned on any biological mutation, drove this demographic explosion. In fact, Reich’s group recently posted noteworthy results showing that natural selection in the genome seems to follow at a lag in the wake of cultural and demographic change, rather than itself being the origination point of new cultural or demographic trends; one dynamic we know well is how lactase persistence as a biological adaptation post-dates by millennia the innovation of dairy consumption. And Reich is among the most eminent geneticists working in the area of human population history, so even his speculative or first-run assessments of emerging data carry significant weight. So what is he getting at? Human history and archaeology show evidence of rapid and explosive demographic changes that seem inexplicable, but could very plausibly and persuasively have been the outcome of technological or cultural shifts consigned to confounding invisibility in the genomic record. When all the evidence comes in, we will probably see that at some earlier date, cultural happenstance drove some particular set of relevant biological adaptations here, which eventually fed into a virtuous circle, in short order leaving our ancestors the globe’s lone survivors.

The aliens like us

A major trend in paleoanthropology over the last twenty years has been the humanization of Neanderthals. That such a campaign was even called for is ironic, given that they are our own species’ nearest kin. But this cultural shift and course correction has been driven by a finding in genetics. In 2010, it became very clear that most humans had some Neanderthal ancestry, with the contribution to our DNA derived directly from this population averaging around 2%. Because of the phenomenon of negative selection against hybridization within the genome, geneticists generally assume the initial proportion of Neanderthal ancestry averaged closer to 10% (Reich recently even mooted a high estimate of 20%). Once modern populations were known to have Neanderthal ancestry, it wasn’t long before Neanderthals were depicted more sympathetically, with gentle expressions, fair skin, blue eyes and red hair. Archaeologists also now believe that Neanderthals were capable of artistic production, something which the field had denied for decades. Finally, we can acknowledge that Neanderthals buried their dead, a ritual whose observance perhaps reflects an awareness of the ephemerality of life, not unlike our species’ own.

But recently, French archaeologist Ludovic Slimak, who has been working at Neanderthal sites for decades, has been making the case that we are now overcorrecting too far in this direction, blurring genuine differences between Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans, turning our cousins into pale reflections of ourselves, and thereby missing the opportunity to gain genuine insights into human minds alien in ways we can scarcely conceive of. One of Slimak’s most provocative contentions is that Neanderthal and anatomically modern human tool-making traditions were fundamentally different. Though Neanderthals made effective tools, they were never standardized, skillfully and cunningly fashioned, yes, but always seeming to reflect creative choices by their individual makers. Tools created by our anatomically modern ancestors have a monotonous but efficient uniformity that distinguishes them from Neanderthal blades. In Slimak’s reading, the indigenous Neanderthals were individualistic artisans, while the intrusive modern humans were collective creatures, prone to producing lines of standardized tools as if they were Paleolithic factory workers.

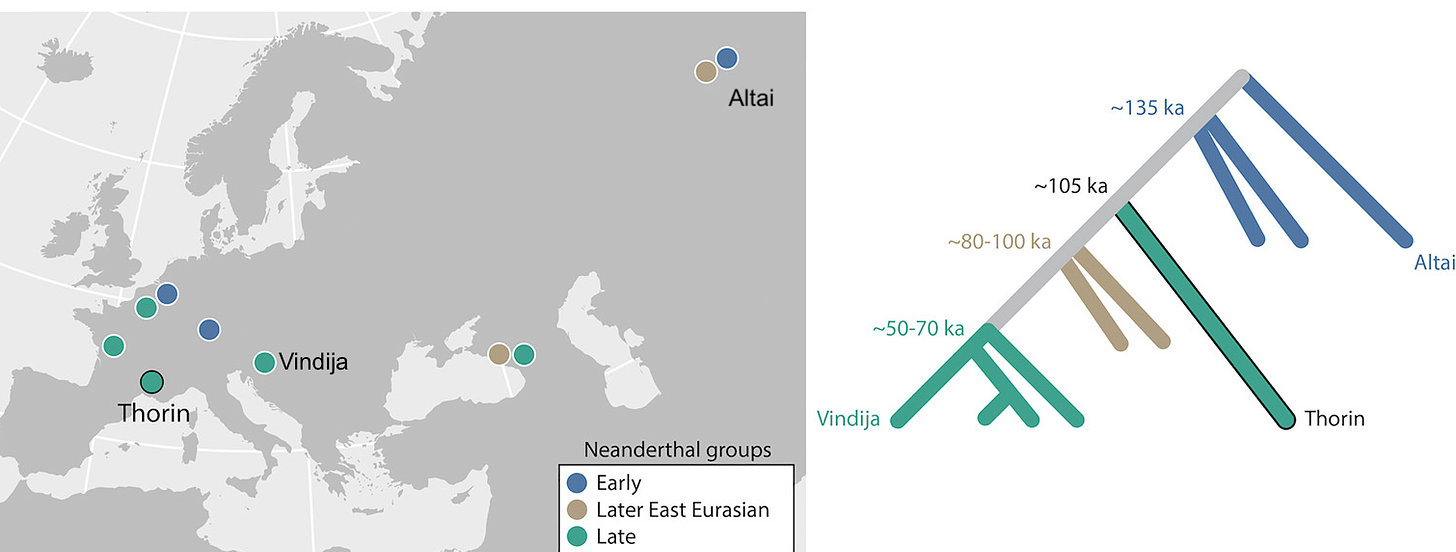

But Slimak’s work has a broader purview than just analysis of material culture; recently his team published a paper elucidating the genetic relationships of a very late Neanderthal dating to ~45,000 years ago in southern France. The source site, Grotte Mandrin, is notable because anatomically modern humans occupied it around 54,000 years ago, four millennia before the beginning of the major expansion of modern humans across Eurasia. Eventually, Neanderthals reoccupied it. Slimak evocatively named the most well-preserved individual at the site Thorin, recalling Tolkien’s character: “one of the last dwarf kings under the mountain and the last of its lineage” while “Thorin the Neanderthal is also an end of lineage. An end of a way to be human.”

Genetics reveals the most surprising thing about Thorin: his lineage diverged from his people’s neighboring contemporary European Neanderthal populations ~105,000 years ago. For over 50,000 years, the genetic evidence shows these isolated Neanderthals did not interbreed with their nearest neighbors even a week’s walk north or east. Intriguingly, Thorin’s genome does have an affinity with some contemporaneous fellow Neanderthals from Iberia, suggesting that southwest European Neanderthals may have interacted more with each other and been a very distinct cultural and genetic group.

Previous to the discovery of the Thorin lineage, Neanderthals were generally understood to exhibit minimal population structure within any given time transect. From the Atlantic to the Siberian Altai mountains, Neanderthal remains kept telling us they had remained genetically quite homogeneous over hundreds of thousands of years. How could this have been? Long-distance gene flow that tied together disparate populations perhaps? Actually, the most persuasive answer seems to be that over the Pleistocene (2.58 million years ago to 11,700 years ago), Neanderthal populations periodically crashed, with most groups going extinct. During each subsequent population bounce-back, a lone Neanderthal population seems to have emerged as the ancestor of all subsequent ones for that cycle. For example, Neanderthals from Siberia before 100,000 years ago seem not to have been the ancestors of later populations there, which were instead genetically derived from European Neanderthals, suggesting a subsequent expansion from west to east.

Thorin complicates this simple model of global expansion followed by local extinctions. Most Neanderthals were genetically more homogeneous within their home populations than anatomically modern humans, indicating small and demographically isolated breeding groups. Thorin’s genetics fits this model, being even more genetically homogeneous than most of the previous (twenty-some) Neanderthals thus far sequenced, with his genome showing evidence of recent ancestors being close relatives. But he also subverts the model of genetic homogeneity between contemporaneous groups at any given time; Thorin’s lineage persisted as a distinct population, despite the great replacement of all Asian Neanderthals by a small European population who actually originated just 100 miles east of Thorin’s group. Thorin’s discovery is perhaps our warning that we still haven’t sampled enough Neanderthal sites to recognize the true proportion of relicts and oddballs, the holdovers from past diversity mostly collapsed and erased during population bottlenecks. Thorin’s existence is proof that the demographic expansions within the bust-boom cycles did not always entail total extinction of earlier lineages.

But for Slimak, among the most intriguing aspects of Neanderthals like Thorin’s population is their stability and lack of interaction with their neighbors. The results from Grotte Mandrin show that Thorin and his ancestors did not mix with their European Neanderthal neighbors 100 miles to the north or east for at least 60,000 years. Looking at the genomes, we know that this was not a matter of hybrid incompatibility, there wasn’t enough time for them to diverge to that point. What seems most likely instead is a strong cultural barrier that impeded the exchange of mates between groups. Genetics of Neanderthal bands indicate that like most human populations, they were patrilocal, with males staying in the group into which they were born. That the genetic differences between on the one hand Southwest European Neanderthals: Thorin’s lineage in southeast France down to the populations in Iberia that stretched to Gibraltar, and on the other, the main Neanderthal populations that stretched from northern France across Eastern Europe and into Central and West Asia persisted for a period longer than the span modern humans have now been in Europe implies that furthermore, they did not even exchange their daughters. Even though modern humans occupied Grotte Mandrin for thousands of years before Thorin’s people recolonized the area, Thorin's genome does not carry any recent trace of the earlier anatomically modern occupants, unlike several anatomically modern European humans from 40-45,000 years ago whose DNA instead bears traces of recent Neanderthal admixture. Thorin was genetically a pure, sapiens-free Neanderthal.

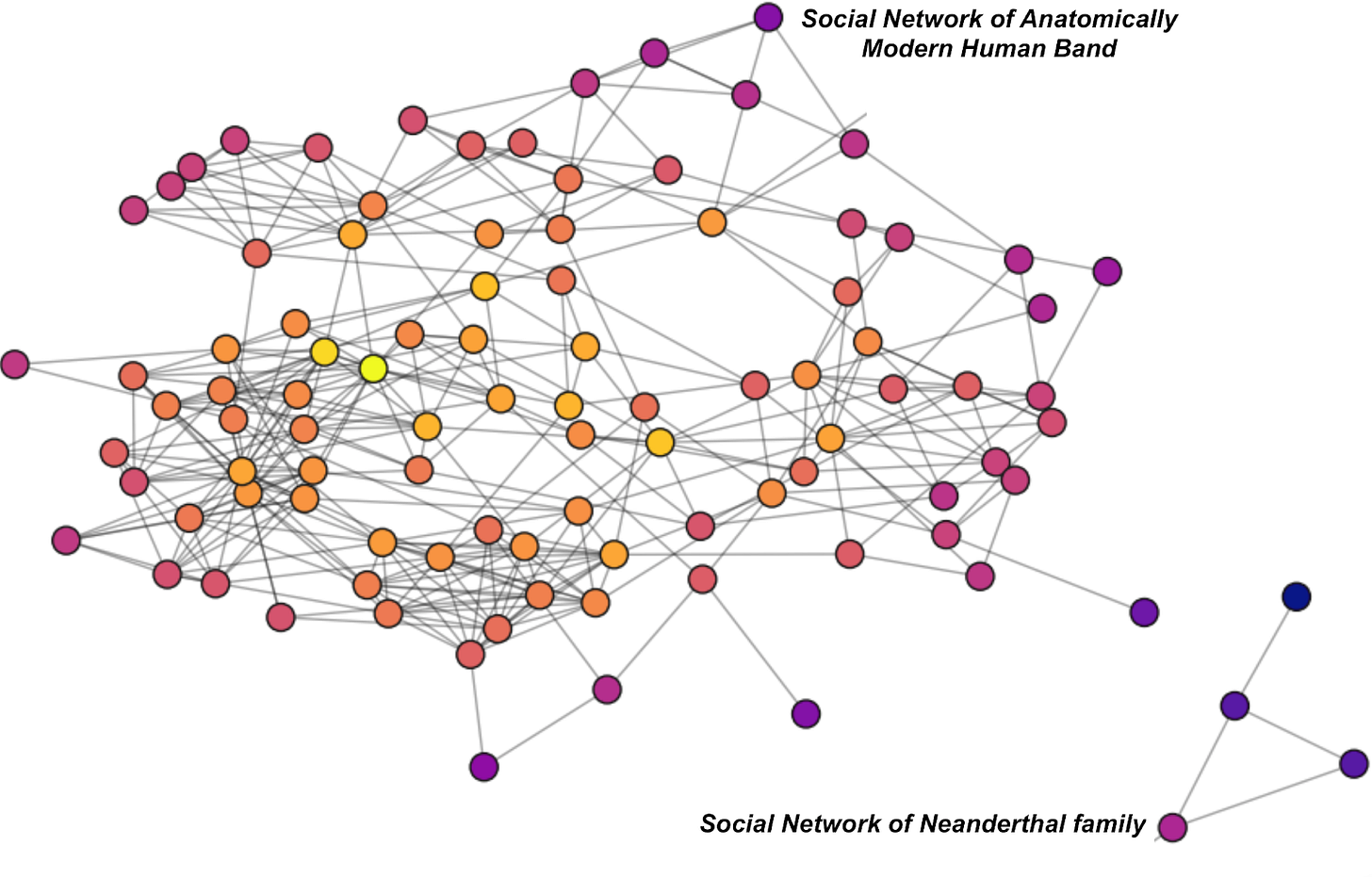

Slimak’s implication is that Neanderthals were a relatively xenophobic branch of humans, while anatomically modern populations were both expansive and assimilative. An aversion to social intercourse among Neanderthals is not entirely shocking when you look at their genes: variants correlated with autism in modern humans are more likely to derive from them than from our anatomically modern African ancestors. Neanderthals famously had brains about 10% larger, on average than our own species, so it is unlikely that they were unintelligent. However, it is quite plausible that they had different cognitive strengths and were comparatively antisocial. And this antisociality is likely the cause of their greater socio-cultural stasis vis-à-vis the human populations coming out of Africa, who proved much more protean and changeable.

Anatomically modern humans spreading across Eurasia and into Australia clearly organized their societies differently from Neanderthals. Genetic results from sites in Upper Paleolithic Europe ~35,000 years ago show the bare minimum of within-band inbreeding, with mates consistently being wholly unrelated to each other, which requires access to widespread social networks. That modern humans absorbed Neanderthals as they expanded illustrates how assimilative and integrative they were. Before ancient DNA, many geneticists and prehistorians assumed that most of the inhabitants of any given area descended from the first settlers who arrived out of Africa. Paleogenomics has disabused us of this simplistic notion, showing instead that replacement, migration and absorption of earlier populations were always a through-line in our story, and indeed probably illustrate something central to anatomically modern human nature.

The demographic big bang

Genetics and fossils have now painted a picture that is more complete and sensible for the emergence of our lineage from Africa and the assimilation of our earlier-arrived cousins in Europe and Asia. Humans who looked like us were present in Africa by 200,000 years ago, if not earlier. They had our distinctive skulls, high foreheads and marked chins, as well as our relatively light builds. But no subset of them washed over the world and replaced Neanderthals or Denisovans with any particular haste. Both evidence of African-human gene flow into Neanderthals hundreds of thousands of years ago, and anatomically modern human remains found outside of Africa over 200,000 years ago, highlight that human populations were long interacting with each other, even if minimally enough to enduringly preserve the broad genetic differences imposed by the geographic barrier of the Sahara that segregated our own lineage from Neanderthals and Deniosvans.

The skulls in Greece’s Apidima Cave that appear distinctly modern human African dated to over 200,000 years ago, thus clinching the reality that our planet has seen many “out of Africa” events; these older populations went extinct or were assimilated into indigenous hominins like the Neanderthals. Though the early bands that were to spread out across Eurasia 50,000 years ago most likely emerged out of the Iranian plateau, where they had mixed with indigenous Neanderthals, these people branched off from an earlier group that went through a many-millennia bottleneck of only a few thousand individuals beginning around 60,000 years ago. Someday, when ancient DNA is retrieved from earlier out-of-Africa migrants to Eurasia, it will lack the marks of this shared history. But the out-of-Africa migration story still holds another subtle twist for us: not all Eurasians descend exclusively from the migratory event that dates to 50,000 years ago, also known as the Initial Upper Paleolithic (IUP) expansion, which reflects the first modern human tool technology to dominate the whole breadth of Eurasia.

The period from 40,000 to 50,000 years ago was a time of transitions in human prehistory, when a million-year-old menagerie was swept away. At the beginning, there were at least two very different Neanderthal populations, many Denisovan groups, and likely several pygmy human species in Southeast Asia. And by the end, not one of them was left standing. In their place, outside of Africa, everyone descended from a single population that had emerged from the mother continent around 60,000 years ago, and everyone left standing emerged from that single fateful bottleneck. The period’s stark turnovers are what led paleoanthropologists like Klein to posit a speciation event to dramatically differentiate us from our hominin ancestors. But over the last twenty years, too many points of evidence undermine the possibility of a speciation event having occurred; both Neanderthal and Denisovan admixture into anatomically modern humans falsify that contention according to the biological species concept which posits an inability to interbreed.

Also, the IUP expansion 50,000 years ago that Klein believed tracked the speciation event did not even impact Africa. Most of the ancestry of modern Africans goes back to populations that had diversified from regional Homo lineages within the continent tens of thousands of years before the IUP expansion. Second, ancient DNA has clarified that both Europe and Central Eurasia saw a second replacement, less than 38,000 years ago. These people were part of the same population that gave rise to the IUP 50,000 years ago, but they hung back some extra millennia, continuing to occupy the highlands of the Near East after their cousins left. And then after 38,000 years ago, in a second migratory pulse, they nearly replaced all Europe and Central Eurasia’s IUP populations, while IUP-descended humans further east became East Asians, Southeast Asians and Australians. The post-IUP modern populations that overwhelmed Europe 38,000 years ago were not genetically so different from the IUP pioneers; and yet they entirely replaced them, just like the earlier IUP populations had replaced Neanderthals and Denisovans.

This pattern of replacement is one we know well, including where the contact is between two populations of modern humans. During the Neolithic, farmers mostly replaced the indigenous foragers. In North America after 1600, Europeans largely replaced the indigenous peoples. In Africa, between 1000 BC and 1000 AD, the Bantu expansion demographically reshaped the continent. In the few millennia between 1600 BC and 1300 AD, Austronesians managed to settle islands along coasts of both South America and Africa, sites some 7000 miles apart, in the pre-modern world’s greatest feat of maritime exploration. In none of these cases, do we make recourse to a genetic explanation. We simply observe currents of cultural evolution, adaptation and innovation, preconditions for what at closer vantage we clearly recognize as often merciless conquests underwritten by one party’s earlier innovation or adoption of powerful new practices.

The preponderance of the data show that in everyday characteristics, culture often drags biology along behind it. Neolithic people developed adaptations to diseases and dietary changes at a lag, long after adopting the suite of novel practices like agriculture and animal husbandry that allowed them to outbreed forager societies. Some have hypothesized that the substantial builds of many Pacific Island peoples reflect selection for those who could survive inclement conditions out on the open ocean, even perhaps the accident of being briefly knocked overboard into frigid waters. The Bantu people’s malaria adaptations swiftly arose in response to their agricultural practices, accelerating the spread of mosquitoes bearing the pathogen.

For anyone wedded to the idea of biological evolution driving culture and not vice versa, a synoptic look over the evidence of the last 50,000 years should be a good corrective: time and again cultural innovations arise that transform individual human societies and reorder the relationships between them. Macromutations and evolutionary jumps might remain exceedingly rare in biology, but they are culture’s classic dynamic. The Neanderthals’ extirpation as much of Northern Eurasia’s main occupants had less to do with new cognitive faculties, and more with a new cultural toolkit that leveraged existent facilities to an extent previously unimaginable.

The rise of the borg

Humans have large brains for our body size (requiring about a third of our calories in resting state) and are capable of incredible feats of cognition that allow us to master bewilderingly unintuitive abstractions like formal mathematics. The Hungarian mathematician John Von Neumann made original contributions to set theory, ergodic theory, quantum mechanics, computer science, co-invented game theory and worked in nuclear physics during the Manhattan Project. And yet Von Neumann has only two grandchildren, meaning that his reproductive output is half of what it needed to be to just replace him (since each grandchild is roughly ¼-related to each grandparent). While precious few humans share Von Neumann’s unique genius in abstruse fields, rare gifts of his caliber do not go to waste, because his fellow humans are, to some extent, all geniuses of sociality and mimicry. It may have required the mental faculties and solitary genius of a Newton or a Leibniz to invent calculus, but hundreds of millions of humans today can integrate by parts and calculate a derivative. To be human is to stand on the shoulders of giants, a privilege underwritten by interconnected social networks.

But human social networks depend on a foundation of innate competencies universal in our species. Anthropologist Robin Dunbar has shown that brain size across lineages of living primates correlates with group size. He argues that we developed superior social intelligence and theory of mind to keep up with the complexity of our expanding and fluid social networks. But his empirical research shows that humans can only keep track of some 150 social connections at once, meaning our native faculties limit the size of the tribe.

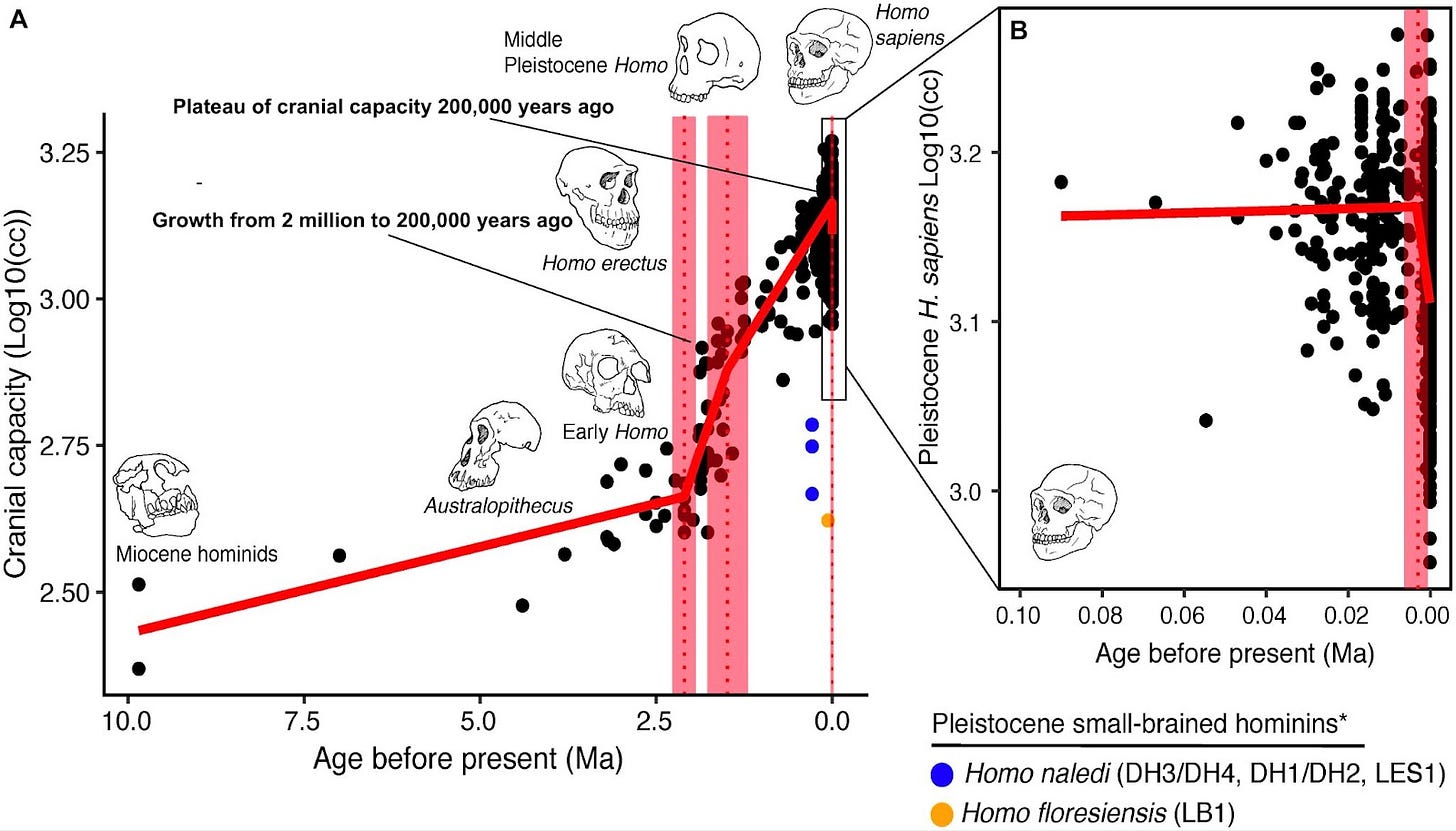

Paleoanthropologists have shown that human brain size, measured via the skull’s cranial capacity in cm3, plateaued 200,000 years ago, likely because of biophysical constraints, whether the ability to safely birth large-brained offspring or the steep energetic cost of ever more neural tissue. Notably, this growth occurred in Neanderthals as well. Whatever was driving this unidirectional change impacted all humans, not just the specific branch that led to us.

And yet evidence is now accumulating that Neanderthal social groups were both smaller and more isolated 50,000 years ago than our ancestors’ were. They simply seem to have been less social than their African cousins. If so, this wasn’t due to any lack of intelligence or more limited brain size. If Slimak is correct, perhaps Neanderthals were even more creative when making tools, likely because they relied more on individual ingenuity and skill. Contemporary anthropological studies show that our species meanwhile tends to mix individual skill-building with social learning and imitation; as toddlers, humans are less capable of individual problem solving than chimpanzees, but then drastically outpace our cousins when learning is predicated on cues and clues from skilled role models. Knowledge and skill are distributed throughout the population, and wisdom passed down more effectively from generation to generation when each artisan does not have to reinvent their particular wheel. But if Neanderthal learning was more individually focused, this would lead to less aggregate innovation, and likely less cultural plasticity, because cultural evolution accelerates via interconnections and engagement between individuals and groups drives exponential changes in human societies.

Social learning and imitation are powerful drivers of cultural evolution. Even in our complex, ever-changing world, imitation remains a cheap and potent shortcut. The USSR developed atomic weapons much more affordably than the US because they had someone to copy. The “China cycle” in economic development explicitly involves imitation, co-option and appropriation, leveraging the earlier innovation of other economies. Because of information technology, the modern world is to a great extent a collective brain, with synergies of innovation across many societies driving aggregate gains in productivity. Maybe this sort of transition, or cultural phase change, was also what marked the rise of our species as lone survivors, a collective borg-brain in contrast to our quirkier Neanderthal cousins with their isolated geniuses and bespoke creations. Rather than individual intelligence, a cultural shift to a collective brain may have occurred. Perhaps IUP humans pioneered mass-production, forgoing individual social status for the more lasting victories of the tribe.

Once this dynamic was in place, winner-take-all dynamics would define all of human history. Biological adaptation often occurs gradually via genetic evolution, but cultural mutations come at you fast and they drive incredibly rapid shifts in norms, customs and skills. We don’t know the specifics of that fateful shift, but 38,000 years ago, the second wave of modern humans in Europe replaced the first, and it was almost certainly because of another winner-take-all cultural shift. The demographic replacement is just too clear and quick. Something similar occurred in Eastern Europe 5,000 years ago, as the Yamnaya and their cousins replaced the last Neolithic Europeans. We know what happened in this case, a combination of disease among the Neolithic people and the Yamnaya embrace of nomadism that allowed them to expand at a trot; indeed the newcomers from the steppe fatefully took over new territories in a few generations.

This had nothing to do with any genetic or cognitive change, but as cultural evolution theorists point out, it is not trivial to adopt one culture’s toolkit in toto, so a major advantage can persist for generations. In the late 19th century, Japan was singular in that it pulled off modernization with an alacrity that left China in this dust; Chinese society was riven by conflicts between traditionalists and modernists and collapsed as a unitary polity. More than a century later, China began to transform and Westernize, but it remains generations behind the West while on many metrics Japan runs ahead. Convergence can occur between two cultures, and we see evidence of late Neanderthals borrowing from and adapting to their modern human neighbors, changing their tool sets through imitation and trade, but ultimately they lacked the innate cultural flexibility to compete against the multiplicative power of our lineage's compulsive sociality and co-operation.

The last 50,000 years have seen a rebalancing of the “dual-inheritance” evolutionary framework, where humans evolve both culturally and biologically. Cultural evolution is ever more capricious and protean, pitting tribe against tribe and nation against nation. Human societies whose evolutionarily inherited social intelligence once limited us to a few hundred members today scale to hundreds of millions, bound by access to widely distributed texts, a fictive kinship beneath a universal God and now ubiquitous social media. The cultural innovation engine inexorably folds in larger waves of humanity with every revolution. And perhaps the undertow that swept away the Neanderthals was just a foretaste of the powerful cultural riptides massing silently under the placid waters in which we collectively live out our lifespans today.