The Unsexiness of Sex Positivity

As sex has become public, it has also become boring. A revival of discretion might be the only way forward.

I first noticed the epidemic of sex positivity when I was a freshman at Stanford. One day after orientation, the entire class is shuffled into the largest auditorium for “Beyond Sex Ed,” which can only be described as a sexual TEDx conference. Student volunteers recount, in graphic detail, some personal experience that the administration judged worthy of being included. My year, a boy described an “adventurous summer” where he tried over 40 partners and was finally penetrated in a public bathroom stall; a girl recalled her most recent encounter in the same voice that one might use to give a valedictorian speech. The event had all the aesthetics of a TED talk, complete with the Patagonia-clad presenters and bright stage lights.

The ostensive purpose of this experience is to introduce students to collegiate sexuality. Instead, I have never wanted to hook up less. It is viscerally disgusting to sit, surrounded by fully clothed classmates, and listen to individuals reveal their deepest sexual selves, all with the tacit approval of the school their parents pay for.

Gen Z and millennials before them are, on paper, the most sexually permissive generations in human history. The same demographic is also having less sex than ever before. These facts should be contradictory––human sexuality was historically repressed and can finally be expressed. In reality, though, sex is now so acceptable that it’s boring. Social propriety watchdogs often try to argue that sex positivity is inappropriate. But they are wrong. It is distinctly, almost painfully, appropriate. To the extent that every generation until ours thought that they invented sex, it is because they had a chance to discover it privately, away from authority figures. We have to discover it with them, which is … gross.

The 1967 “Summer of Love” was mostly a marketing scheme, but the name stuck because it captured a massive sentiment change: After centuries of shame and repression, virginity tests and the expectation of missionary-only monogamy, the rules around sex were finally breaking down.

By the mid-1970s, the extremities of “free love” had run their course, and some communities were beginning to feel tinges of sexual exhaustion. In her 1974 essay “Fascinating Fascism,” Susan Sontag described an unusual practice then emerging among gay men. They were meeting in dungeons to hurt each other during sex. The gay leather underground pulled liberally from fascist aesthetics—the whips and chains, as well as the rigid leather, were all reminiscent of SS uniforms. Sontag mused that fascism was perhaps the last erotic frontier, the only remaining way to be truly subversive in a sexually liberal milieu.

BDSM was far from the dominant sexual experience of the decade, but its practice exemplified the urge to have slightly more, in sex and in the rest of life, than whatever is readily available: more sensation, when the old sensations became tired. More people. More risk. More pain.

A vibrator is a useful symbol for sex without personhood, a version of sexuality that is desperately trying to extricate itself from universal human desires.

In the 1980s, the AIDS crisis put a temporary damper on no-strings-attached experimentation. For the last time in recent memory, sex intertwined with death, and disease, and the wrong kind of risk. The so-called Moral Majority took a last stand in the Reagan era, perhaps sensing that public sentiment was slipping from their grasp. In popular culture, however, a second sexual revolution was still underway. Feminist leaders like Andrea Dworkin and Catharine MacKinnon had historically shunned pornography, and most heterosexual sex, as a violation of female autonomy. But women increasingly found the movement’s rigid anti-eroticism, anti-man posture to be out of step with their actual desires. A new wave of sex-positive feminists argued that pleasure, far from being a tool of male oppression, was actually an act of radical self-love.

The porn wars ended with a whimper, and the cause du jour among feminists became that men still don’t know where the clitoris is.

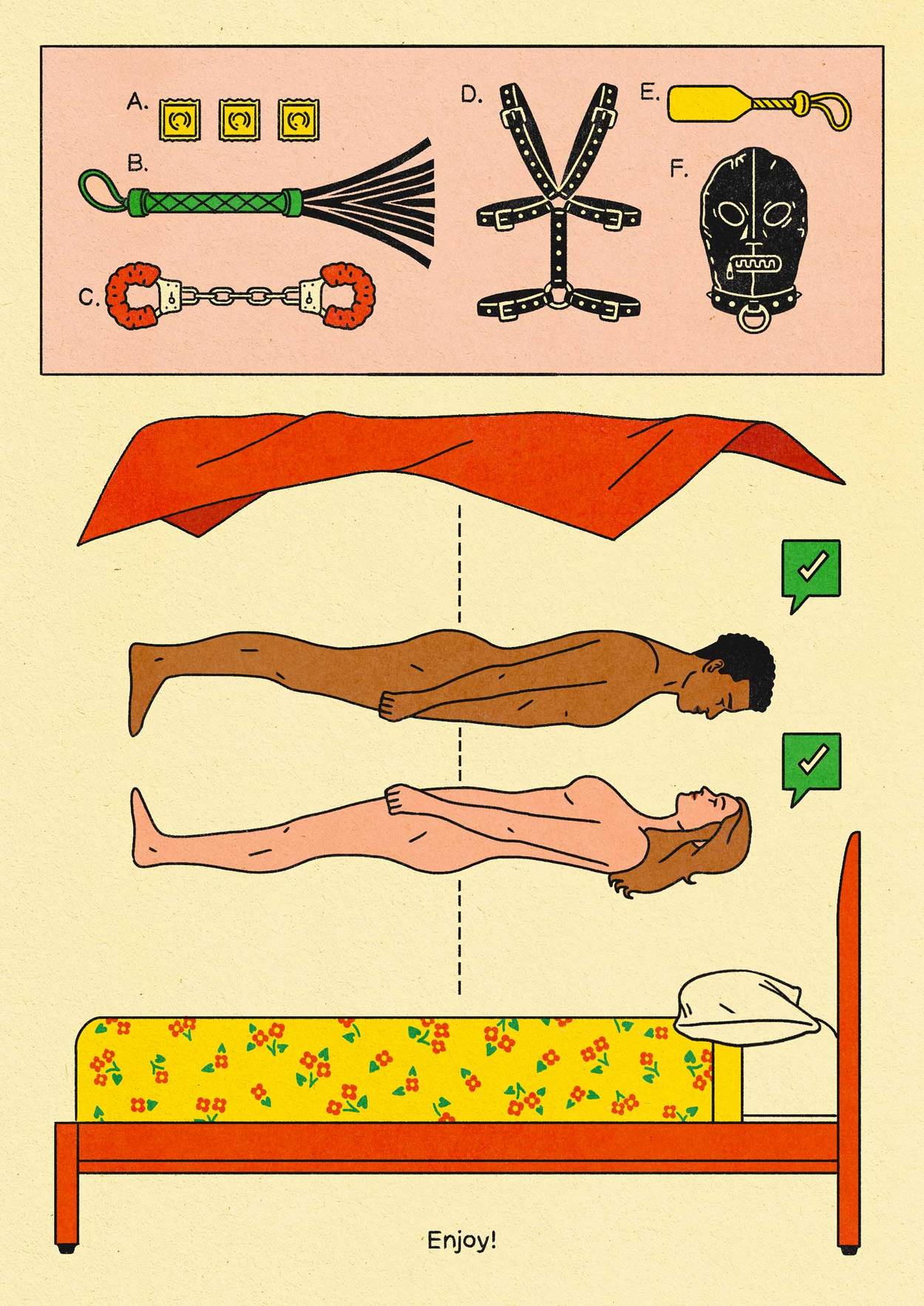

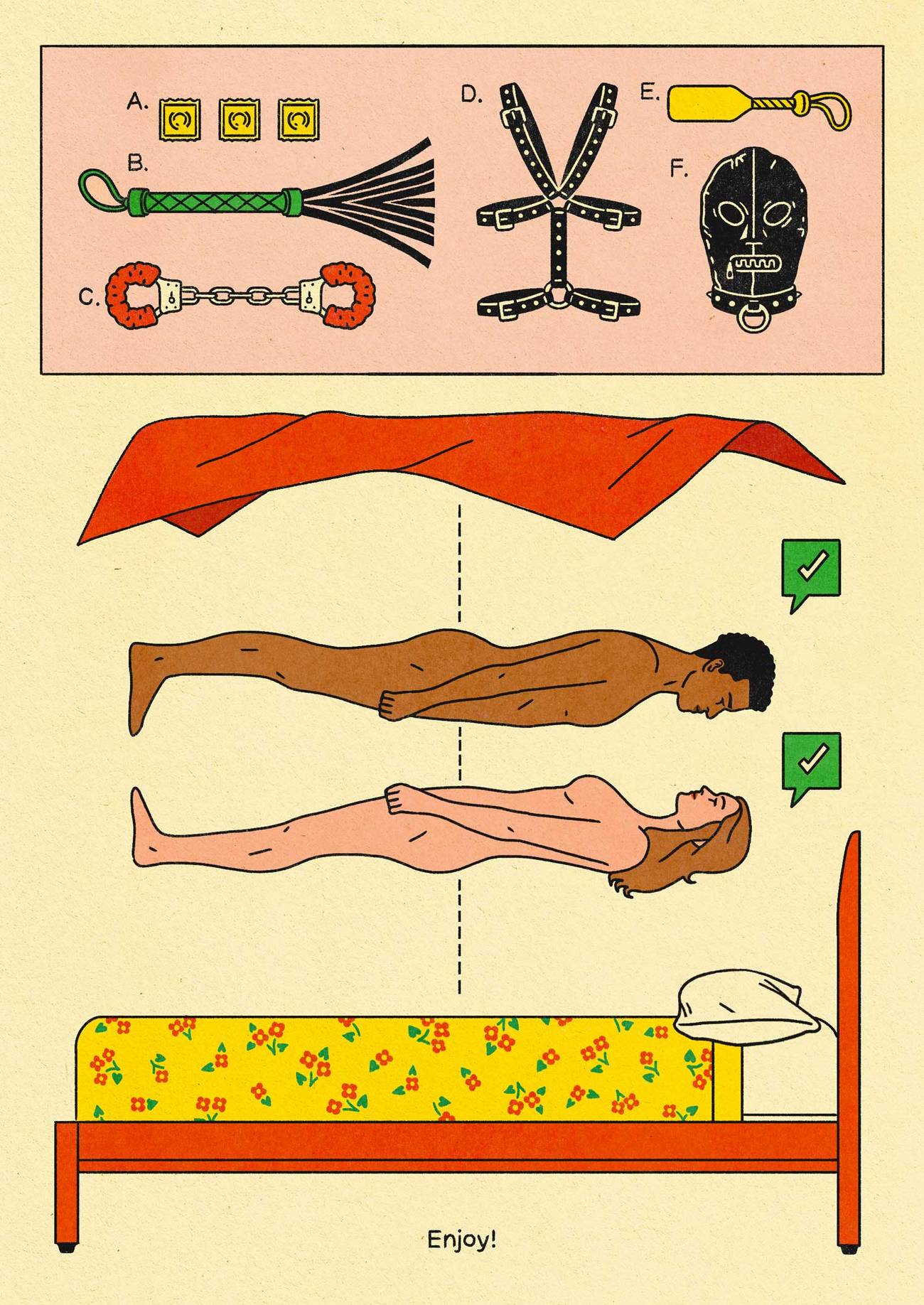

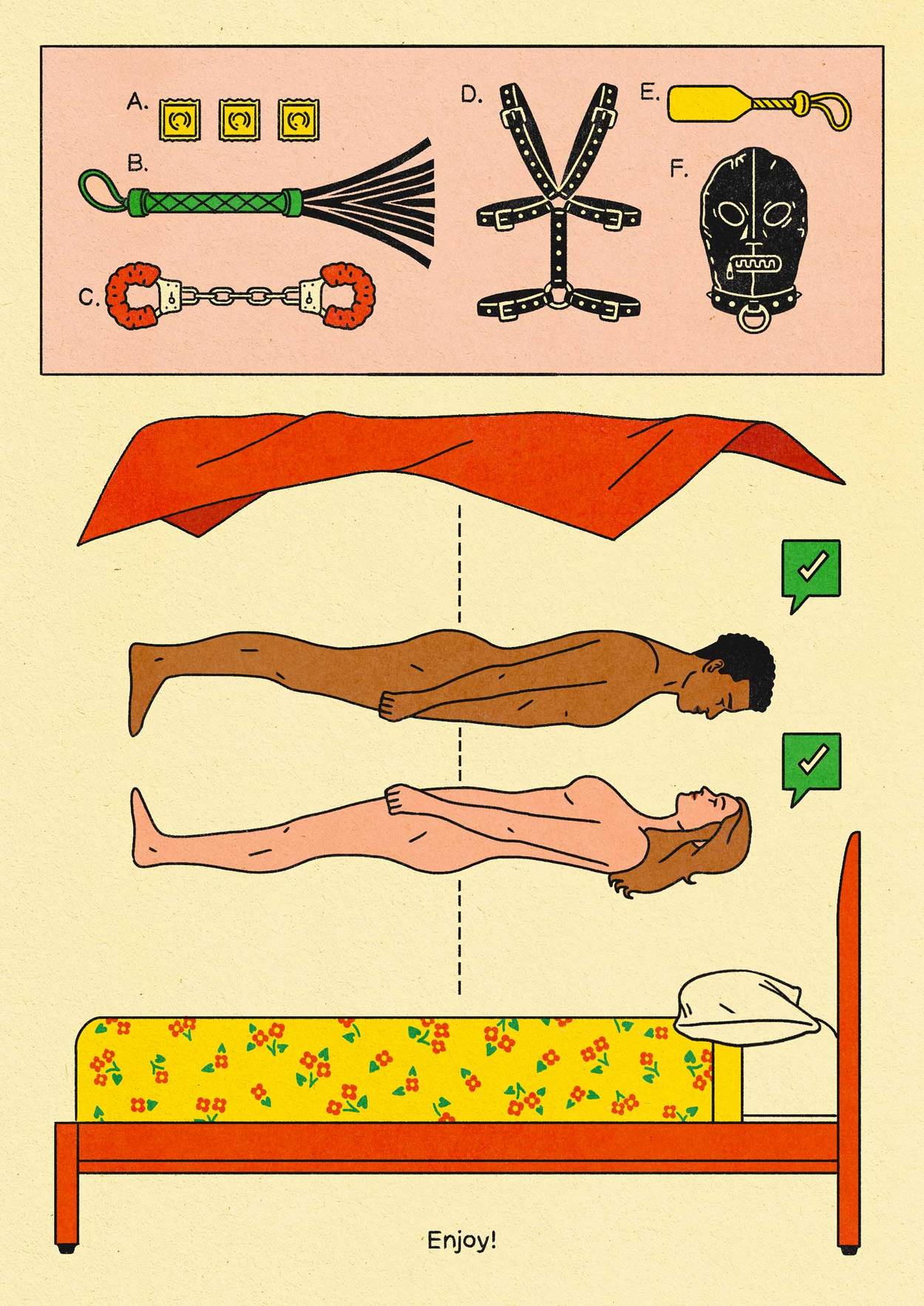

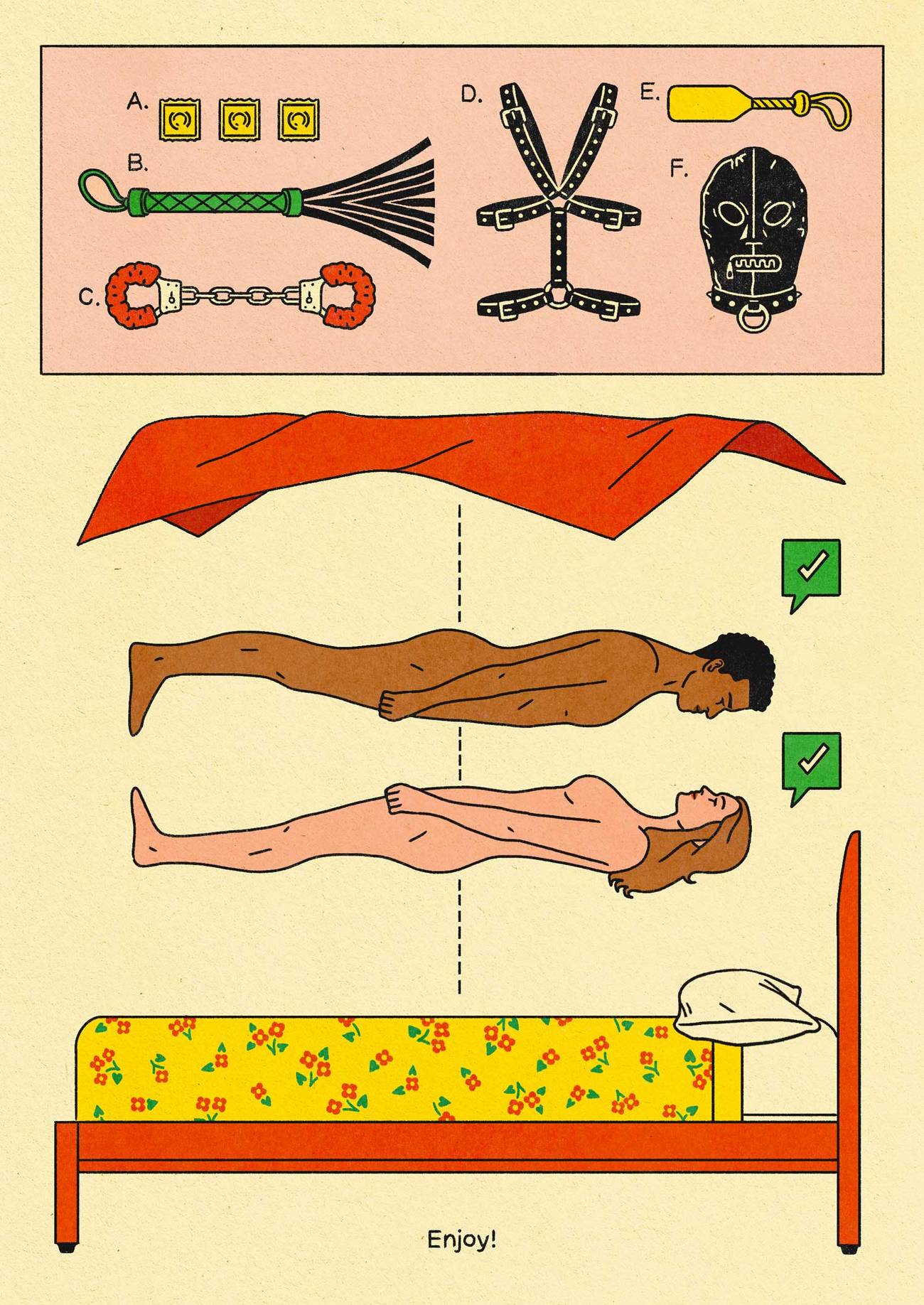

Sex positivity hit the mainstream in the early 2010s, alongside the rise of popular, hyperconsumable infographic feminism and the widespread embrace of social activism. If you are a woman and have a phone, then you are likely familiar with the aesthetic: BuzzFeed-style kink quizzes and designer sex toys. The ostensive purpose of these displays was to destigmatize sexuality on behalf of women, who, sex positivity argued, still needed to have our anatomy explained to us by orgasm guides and vulva-shaped cupcakes. But the same impulse—for less shame, more exposure, and lots of detailed explanation—could be easily applied to all genders. The current iteration of sex positivity seeks to normalize the full spectrum of sexual acts by reducing them to their most technical details—the mechanics of a novel position; the price of a personal flogger. The result is a sexual uncanny valley replete with all the visual indicators of sexuality (whips! harnesses! butt plugs!) and none of the electricity.

Today, sex positivity has successfully rebranded sex as just another facet of self-maintenance, like brushing your teeth or choosing the right moisturizer. But what sex positivity denies is that many of the behaviors it seeks to destigmatize never sought to be “normal” in the first place. Bondage was explicitly designed to subvert; instead, it has been cleaned up and rebranded as yet another equally valid sexual option, commodified in kink contracts and commercialized on Netflix shows like How to Build a Sex Room. For today’s teenagers, browsing Teen Vogue-approved ethical porn is far less exciting than stealing your dad’s copy of Playboy.

Actual sexual content can either arouse or disgust: It is, or it is supposed to be, charged. Far from inhibiting sexual satisfaction, insinuations of wrongness create a fascination that obscures the simplicity of the act itself.

To some extent, all of sexuality is at war with a fundamental banality––the limits of the human body, which is mostly the same every time. Kids, lacking the hormones to be interested in sex, find it disgusting. Which it is, objectively. When you are younger, any interest in the subject comes from simple curiosity––sex involves parts that you have never likely seen before and which adults will tastefully not allow you to look at. As we grow up, we gain the ability to feel attraction, but much of that intrigue is lost.

Everyone has a body. Bodies can be appealing, but they can also just … exist, as relatively uneventful flesh vessels that are easily rendered lurid with a bright enough light. That is the purpose of lingerie, and the ubiquitous role of shadow in erotic visuals––to add some novelty, and artificial blockers, to an object that can otherwise only do so much.

Today, it is difficult to make a moral argument against particular sexual acts. God will not strike you down for an unfortunate encounter, and the pill has gotten rid of most practical constraints around premarital sex. And yet, for all our stated comfort with bodies, sex positivity itself is somewhat of a false flag, celebrating the physical act of sex while hiding from the impetus for sexual attraction.

Sex positive content is promoted by educational institutions, major newspapers, minor celebrities, and more than a few venture-capital-backed lube companies. But why would a society that is increasingly uneasy about sex be obsessed with putting sanitized versions of it everywhere? Sex positivity exists, seemingly, to square two contradictory and ascendant strands of liberal thought. The first goes that consensual sex is an unequivocal good––pleasure is a human right, and our personal preferences are near sacred. We must tear down shame to unleash our innate sexual selves. And the second is a growing concern about why, exactly, people want to have sex with each other. Despite our best efforts, the so-called “conventionally attractive” among us (slim, wealthy, powerful) still hold a near-monopoly on actual sexinesss—an unearned advantage that sex positivity advocates, and general proponents of fairness hope to demolish. It is a fine line to walk: Sex is good, and all preferences are valid, but it might be better if people liked something else.

Young people are not changing their preferences so much as denying that they exist. We are uncomfortable with our physicality, we are uncomfortable with any romance that does not fit a particular script, and more than that, we are deeply uncomfortable with sexiness, and the often uncontrollable nature of desire. And so in place of love stories, or actual sex symbols, we seem to have generated a lot of content about sex—celebrating the physical act, performed abstractly by other people.

To create sexually appealing content, you have to present an object of desire and intimately understand its appeal. The author Sally Rooney has received a lot of hate recently, but there is a reason why her work is widely cited as the first great millennial love story—she is not afraid to explore, in painstaking detail, the why and why not of loving someone. These realistic depictions of relationships have won her wide acclaim, but they have also upset a demographic that would prefer not to have their proclivities reflected back to them so clearly.

It is the details of a connection that make sexuality worthwhile. And yet portraying that specificity is increasingly fraught, and rare.

Sexual preference is not a roulette wheel: Who we want is intimately tied up with the physical markers of age, ability, race and class. The contemporary sexual ethic is increasingly removed from actual stimuli. We support sex, but have little to say about beauty. We respect personal preference, but still squirm when a young woman poses in a flattering light and receives sexual attention from men.

The best way to resolve that contradiction is to alienate viewers from the who and the why of an encounter. Perhaps that is why most sex-positive content features a lot of vibrators. A vibrator is a useful symbol for sex without personhood, a version of sexuality that is desperately trying to extricate itself from universal human desires.

For now, we are at a crossroads: There is no lack of sexual content on offer, but none of it is particularly sexy. Celebrities, likely recognizing the low cultural regard for content about sex, are increasingly unwilling to participate in its creation. It is possible that frustration with years of constant, overt displays of sexuality will eventually create a backlash that reasserts some old taboos––if only so they can be broken again. Or perhaps sex positivity, and the visible celebration of sexuality, is simply the end of a long march toward demystification that ends with disenchantment.

A more honest accounting of sexiness could result in sexual content that is, if less mysterious, at least more visually appealing. And in the meantime, there is one simple solution to the current crisis of sexual malaise: a revival of discretion. We might all be better off removing explicit sexuality from the public eye—not because sex is wrong, but because by flattening all distinctions between it and the rest of life, we may destroy what simple pleasures it had to offer.

Ginevra Davis is a writer working in art and design. She writes about technology and youth culture.