We need your help! Join our growing army and click here to subscribe to ad-free Revolver. Or give a one-time or recurring donation during this critical time.

The Anglo-American common law was supposed to save Derek Chauvin. That it failed to says a lot about the America we all actually live in now.

It’s been two and a half years since the former Minneapolis police officer was convicted of murder for the death of drug addict and lifelong criminal George Floyd. Chauvin is barely one-tenth into his twenty-two-year prison sentence, which he is serving concurrently with a 21-year federal sentence for depriving Floyd of his “civil rights.”

The Chauvin verdict was an obvious, sick joke from the moment it happened, but even on the American right, the full realization of this fact seems to have taken until the last few weeks.

Helping to lead the charge was Fox host-turned-X-titan Tucker Carlson, who highlighted little-noticed recent developments in the Chauvin aftermath.

Ep. 32 You’ll be shocked to learn this, but it turns out the whole George Floyd story was a lie. pic.twitter.com/4vDXBStHf5

— Tucker Carlson (@TuckerCarlson) October 20, 2023

The developments in question stem from a lawsuit by Hennepin County prosecutor Amy Sweasy Tamburino. Tamburino’s lawsuit claimed her career stalled out due to sex discrimination in the Hennepin prosecutor’s office. But the evidence in her lawsuit overlaps with the Floyd case, and in fact, reading between the lines, one can sense the real reason Tamburino is suing the county: Higher-ups sabotaged her career because she didn’t play ball in the Floyd case.

Case files include a deposition from Sweasy in which she mentioned a conversation with the county’s medical examiner, Dr. Andrew Baker, after he performed Floyd’s autopsy.

In the Carlson clip, text attributed to Sweasy read: “I called Dr. Baker early that morning to tell him about the case and to ask him if he would perform the autopsy on Mr Floyd.

“He called me later in the day on that Tuesday and he told me that there were no medical findings that showed any injury to the vital structures of Mr. Floyd’s neck.

“There were no medical indications of asphyxia or strangulation.”

Carlson then said: “In other words, George Floyd, according to the official autopsy was not murdered.” He added that Floyd died of “natural causes, which in his case would include decades of drug use, as well as the fatal concentration of fentanyl that was in his system on his final day.”

But Revolver isn’t here simply to echo Carlson’s excellent reporting. Instead, a crucial point must be made. The fact that Chauvin is now spending decades behind bars shows the terminal decay of one of the few institutions seriously protecting Americans from the overreach of an authoritarian state: the jury system.

The flaws in the criminal case against Chauvin and the real facts about his death are the sort of things that a competent jury should have deduced. The state of Minnesota might have brought a parade of “experts” to testify that “asphyxiation” killed George Floyd, but a competent jury would have seen through this and gone straight to the medical examiner’s initial autopsy, which plainly states the opposite.

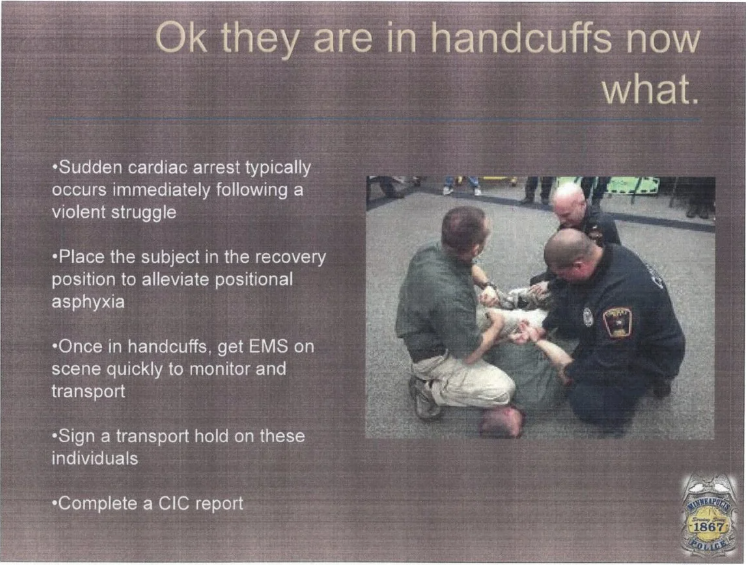

A competent jury would have seen through the swarm of ass-covering bullshit from Minneapolis police, who muddled the issue by claiming that Chauvin’s knee restraint on Floyd wasn’t a part of department policy when Chauvin’s defense attorney had a literal photo proving otherwise.

A competent jury would have realized that if Floyd was able to talk with Chauvin’s knee on his neck and if it took him more than 4 minutes to lose consciousness, then it followed that Chauvin’s knee was not choking or strangling him and some other force caused his death.

But they did not.

Instead, post-trial interviews with Chauvin jurors reveal that the jurors not only misunderstood basic facts, but that facts barely mattered to them at all. Instead, jurors engaged in emotional babble about how they felt Chauvin didn’t “care” enough about Floyd.

In the jury room, Belton Hardeman said, she recalled testimony about a Minneapolis police motto: “In our custody, in our care,” or words to that effect.

“George Floyd was in their custody,” she said. “He was never in their care. And that for me … it just hit hard. I don’t feel like they ever cared for him.”

In an interview with ABC, juror Brandon Mitchell said that yes, of course, the jury definitely treated Chauvin’s refusal to testify as evidence of guilt.

“It probably was to his detriment that he didn’t take the stand because people were curious on what his thoughts were throughout the entire incident,” Mitchell said.

That same juror, incidentally, had attended a 2020 BLM rally wearing a “Get Your Knee Off Our Necks” T-shirt.

Should this surprise any of us? Hardly. The American press did extensive research on all the jurors (in case any of them had to be declared a public enemy after a mistrial or, God forbid, an acquittal). The tidbits of information they released during and after the trial make it plain Chauvin’s fate was determined by clueless idiots.

The Washington Post kept tabs on all the jurors in what was the “trial of the century” for liberals:

Juror #44 — White woman, 50s- An executive at a nonprofit health-care advocacy group and a single mother to two teenage boys, the juror said she discussed White privilege with a Black co-worker. The co-worker’s son is the same age as the juror’s older teenager. “But my White son, if he gets pulled over, doesn’t have to have fear.”

…

Juror #55 — White woman, 50s- A single mother of two who rides motorcycles in her spare time, she described being scared by the unrest that gripped Minneapolis last year. She also mentioned seeing officers confront an unarmed White teenager last summer, calling it “harassment” and saying that when she tried to intervene, an officer ordered her to stay back.

…

Juror #27 — Black man, 30s – An immigrant who came to the United States more than a decade ago, he once lived near where Floyd was killed. The man said a friend showed him the video of Floyd’s death; afterward, he told his wife: “It could have been me.”

Just what America needs: jurors who see a nine-times-convicted druggy shuddering off the mortal coil while committing yet another crime while high and think, “Gee, that could be me!”

In the past, it was well understood that the strength of the jury system derived not merely from the practice of having a jury but also from assuring the quality of the jury.

In early modern England, a man accused of a crime wasn’t merely expected to benefit from a jury, but specifically a jury of freeholders—that is, men who owned their own land and, by extension, had financial independence.

After the Glorious Revolution of 1688, the English revolutionaries issued the Bill of Rights of 1688, which stated the grievances they said justified the overthrow of James Stuart. Among them: gutting the quality of juries.

The English Bill of Rights 1689:

And whereas, of late years, partial, corrupt and unqualified persons have been returned and served on juries in trials, and particularly diverse jurors in trials for high treason, which were not freeholders … all which are utterly and directly contrary to the known laws, statutes and freedom of this realm. … Therefore, the parliament, for the vindication and asserting the ancient rights and liberties of the people declare … That jurors ought to be duly empaneled and returned, and jurors which pass upon men in trials for high treason ought to be freeholders.

Throughout the 18th century, English law required that a juror possess lands with an income of at least ten pounds per year, a figure that excluded two-thirds of the male population.

This expectation that a criminal jury would be a jury of freeholders existed well into the existence of the United States.

Most Americans know that the Sixth Amendment guarantees the right to a jury trial in all criminal proceedings. But when Roger Sherman of Connecticut proposed his own initial draft of the Bill of Rights, he proposed an even more specific right as a possible third amendment.

“Text of Proposal for a Separate Bill of Rights”:

No person Shall be tried for any crime whereby he may incur loss of life or any infamous punishment, without Indictment by a grand Jury, nor be convicted but by the unanimous verdict of a Petit Jury of good and lawful men freeholders of the vicinage or district where the trial Shall be had.

From the start, America’s property requirements for jury service were more lenient, simply because land was so much more plentiful in America and so truly landless individuals were less common. Still, such requirements lasted far longer than most people realize. New York only abolished all property requirements for jury service in 1967. Texas only abolished them in 1969, meaning property standards for jurors are more recent than the White Album by The Beatles.

These requirements were a lot more than mere snobbery. A juror with a firm source of income would be harder to bribe or intimidate. In an age where any living could be precarious, jurors who could sustain a financially independent household were more likely to be reasonable and grounded. They would be better situated to resist popular hysterias, and they’d be invested enough in the system to not nullify the law out of sympathy for criminals. However imperfectly pursued, these traditions represented an ideal: A juror shouldn’t simply be a random person, but a capable one who, alongside 11 others, would be able to deliver impartial justice.

Today, this ideal might as well be dead, strangled (unlike George Floyd) by a new political ideal that holds that all adults from anywhere on earth are equal in all things, including their ability to deliver a fair verdict in a sensational murder trial. And so, whatever the law says and whatever justice might dictate, every murder case that goes to trial is a roll on the roulette wheel. Sometimes, things work out, like when Kyle Rittenhouse went free. And sometimes, things go horribly wrong. At this moment, William Bryan is serving a life sentence because he saw “jogger” Ahmaud Arbery being chased, assumed he was a fleeing criminal, and tried to help detain him, only for Arbery to be shot to death after attacking and trying to grab the gun of a pursuer. Bryan never carried a gun nor sought to commit any crime, but thanks to a Georgia jury, he will likely die in prison.

Even in cases with the right outcome, statements by jurors after the fact can leave a jarring impression. For instance, in 2013, a member of the George Zimmerman jury opined that, in her heart, she thought Zimmerman was a murderer.

“George Zimmerman got away with murder, but you can’t get away from God. And at the end of the day, he’s going to have a lot of questions and answers he has to deal with,” Juror B29 told ABC, according to an article posted on the network’s website Thursday. “(But) the law couldn’t prove it.”

The juror, who used only her first name of Maddy out of concerns for her safety, told ABC that she and others on the panel felt Zimmerman was guilty, but that wasn’t enough.

“You can’t put the man in jail even though in our hearts we felt he was guilty,” she said. “But we had to grab our hearts and put it aside and look at the evidence.”

A subsequent profile of the same juror by The Daily Beast makes it even more appalling that she once held a man’s entire life in her hands:

As a nursing home caregiver, Maddy had no experience with the American court system, which seemed alien to her, conducted in a harsh foreign tongue. While being questioned at length by meticulous defense attorney Don West during jury selection, she felt confused and intimidated—

Was she on trial? What had she done wrong? Why did he keep asking her what TV shows she watched, what newspapers she read?

Was he accusing her of lying? Of being stupid? “They made me feel so guilty of something I didn’t even do,” she said. Only bad people had to go to court, she believed—just being in the courtroom made her feel like she must have done something wrong. “I don’t know who George Zimmerman is, I really don’t!” She kept telling them, but they kept asking anyway, the same question from different angles, because they wanted to be sure to seat jurors like Maddy who had not been tainted by pretrial publicity. It was exhausting her. The unnerving way Don West looked directly at her, as if he could read her mind—she’d never experienced anything like it and hoped never to feel so cross-examined again. “He scared the hell out of me. I cried when I came out [of jury selection],” she said.

A woman who cried during voir dire made it onto a Florida jury for a murder case.

Now consider that, sometime next year, Donald Trump will go on trial in Florida in a complex federal case involving interpretation of federal statutes and an unprecedented application of federal records laws to a former U.S. president. Imagine if the verdict comes down to a confused nursing home caregiver who can’t quite understand English and doesn’t know how a court works.

And yet, despite all of this, the jury system, by its very existence, is one of the few protections an American dissident or patriot has. Anyone who entrusts his fate to an American jury is rolling the dice on the emotional “gut” feelings of a random selection from America’s rapidly deteriorating human capital. This unfortunate devolution recalls the old medieval “trial by ordeal,” in which the accused was subjected to tests like being submerged in water, burned, or forced to ingest poison. The premise behind such trials was that God would intervene and protect the innocent from harm.

Today’s trials are an ordeal of their own, but instead of fire or poison, the test is whether one can survive being judged by randomly-chosen 50-year-old single moms working at non-profits or borderline illiterate recent immigrants.

The truly sad reality is that this random selection still offers better treatment than one will get from a system that is determined to annihilate its political enemies.

That might be the toughest pill of all to swallow: That in modern America, the friendliest institution one has is the one that runs on dumb luck.

SUPPORT REVOLVER — DONATE — SUBSCRIBE — NEWSFEED — GAB — GETTR — TRUTH SOCIAL — TWITTER

Join the Discussion