We need your help! Join our growing army and click here to subscribe to ad-free Revolver. Or give a one-time or recurring donation during this critical time.

Fashion should embody timeless beauty, captured in the delicate flow of chiffon gowns and the gallant elegance of men’s suits that define worldly masculinity.

Fashion should be living, breathing art with a pulse and a soul, not a weapon used to crush Christianity, destroy tradition, and blur the lines between good and evil.

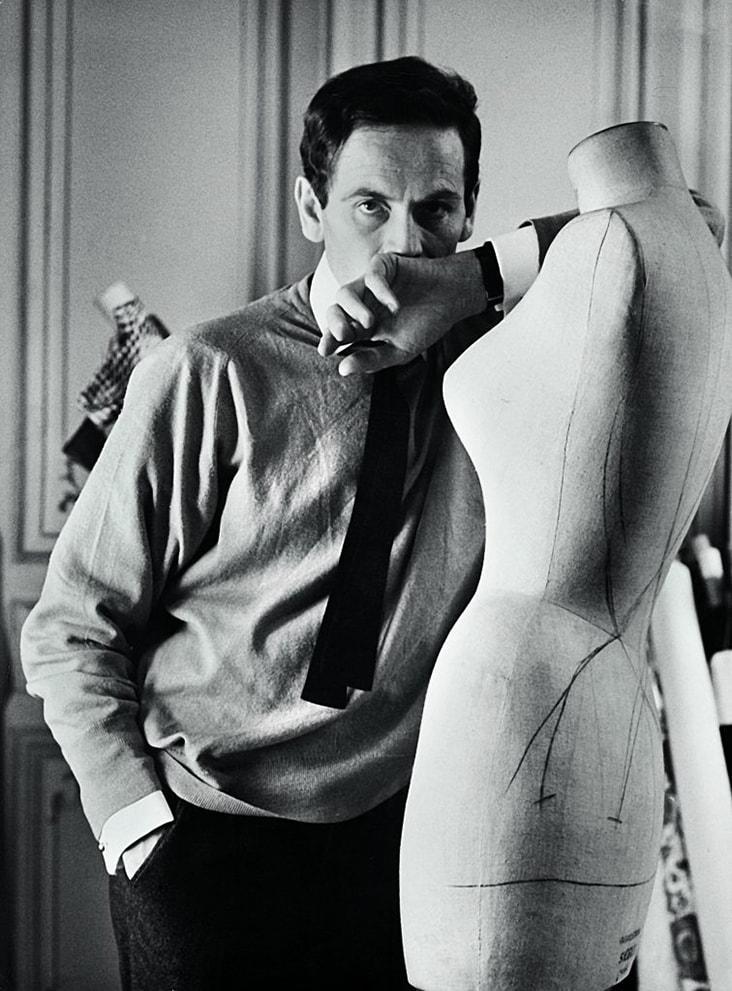

But that’s precisely the opposite of what happened in the last century, all thanks to a godless man by the name of Pierre Cardin—a legendary fashion designer who has done more to dismantle traditionalism than even Satan himself could conceive. To emphasize the point, Pierre’s doppelgänger was none other than the ’70s serial killer Ted Bundy.

How fitting. Pun intended.

So, who was this narcissistic man dedicated to erasing beauty in all its forms? Pierre Cardin was born Pietro Costante Cardino in 1922. He was an Italian-born, naturalized-French coutierier. Cardin was one of ten children born in northern Italy. His parents were extremely wealthy wine merchants but lost their fortune during World War I. Consequently, in 1924, they packed up and fled to France to escape the blackshirts.

Pierre’s father encouraged him to pursue architecture in Saint-Étienne, France. However, young Pierre always aspired to be a fashion designer. So, after World War II, he dove headfirst into the world of fashion and never looked back.

Cardin would die 98 years later, in December 2020, in a Paris hospital room. His cause of death was never made public, but at that ripe old age, what difference does it really make?

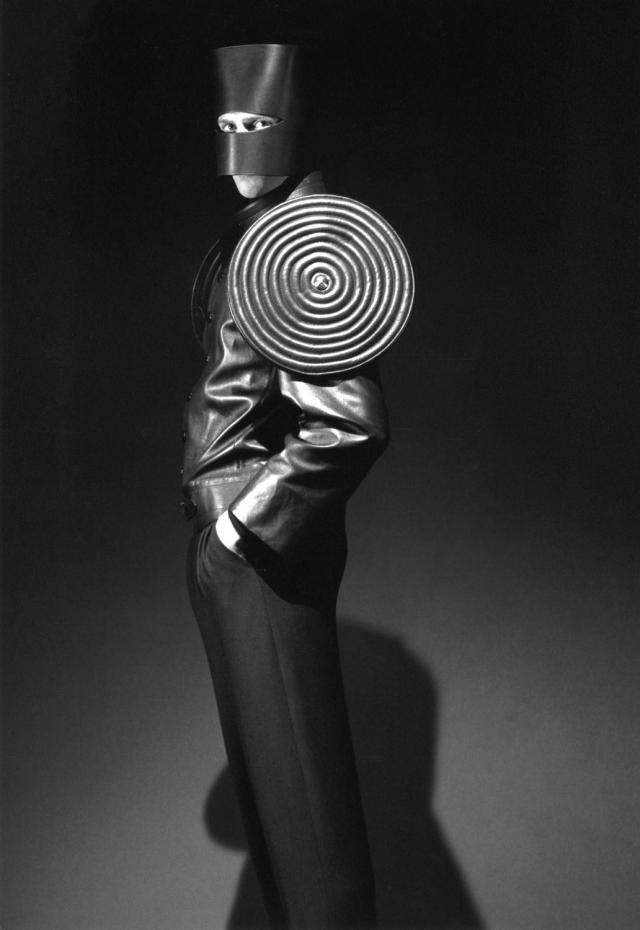

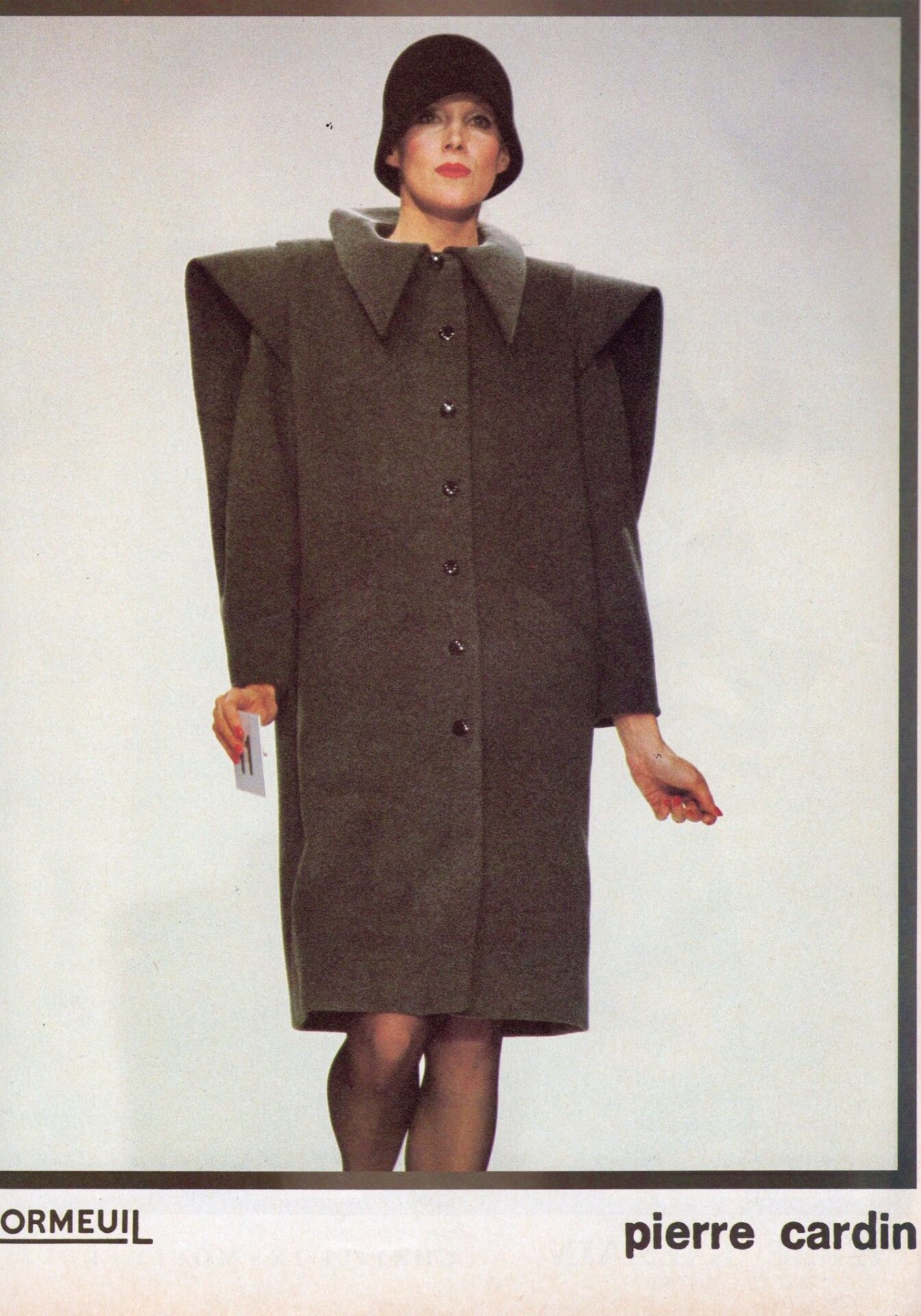

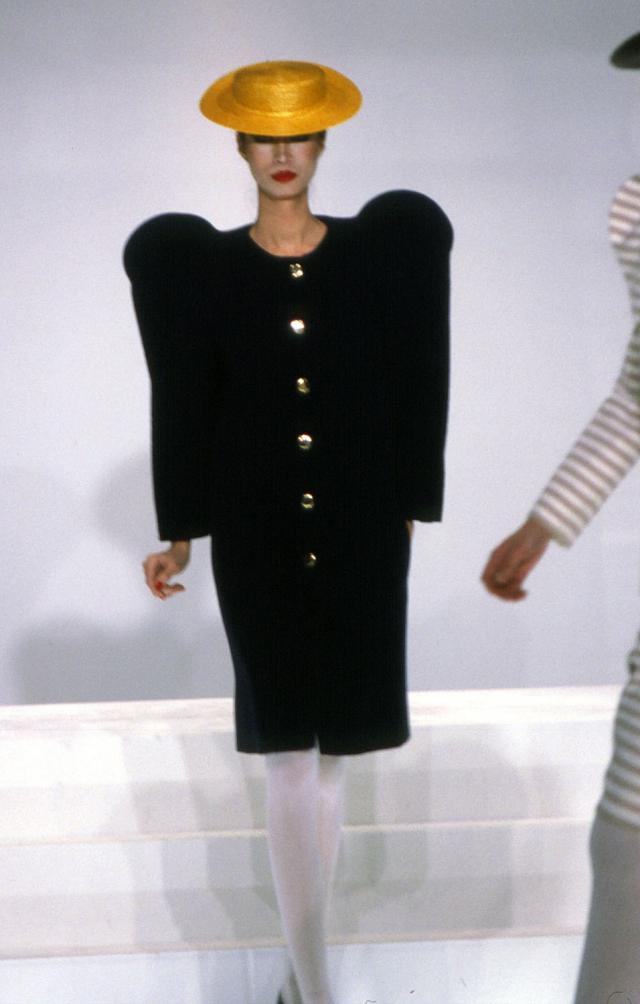

At first glance, Cardin’s legacy includes industry-changing licensing agreements, ugly avant-garde styles, and Space Age designs. Cardin had a fascination with geometric shapes, often leading to designs that veiled the traditional female silhouette in favor of more abstract, unconventional forms, some of which appeared provocative or reminiscent of S&M aesthetics.

However, there was more to this complex and arrogant designer than his repugnant design looks. He was on a mission to erase tradition from the face of the earth and replace it with a futuristic, agnostic society of genderless freaks. Cardin once stated, “I was very lucky; I was part of the post-war period when everything had to be redone.”

Indeed, he played the role of a self-appointed deity, using fashion to “redo” everything. This obsession explains why Cardin was a pioneering force in the push to redefine masculinity. He harnessed fashion to blur the lines between men and women, leaving both sexes in shapeless ambiguity. He was yet another fashion legend obsessed with gender and androgyny.

Pierre Cardin […] claimed credit as not just the first unisex designer, but as the first true menswear fashion designer in all of history. Nothing that came before him was fashion (in his opinion)—Cardin claimed his brand and aesthetic would wax and wane, yet ultimately prove eternal. He mythologized himself in real-time, invented, stoked, and conquered every controversy in the press, and constantly thought of the Future not as a temporal moment far ahead of us in time, but as a physical object—a category of objects—made to be sold, and appropriated by the owner to construct a readily readable social and cultural identity.

Cardin’s ultimate legacy may not be the creation of a totally timeless forever brand for the whole family, a full lifestyle, as he famously wished it to be. It’s arguable that, instead, Cardin should be remembered for ushering in a new era of apolitical unisex fashion, which offered itself up as a sacrificial strawman to a conservative culture obsessed with defining new justifications for the siloing of masculinity and masculine aesthetics into distinct and stable categories.

Regrettably, Pierre’s corrupting influence continued to wreak havoc on generations. Surprisingly, many of you reading this have unknowingly encountered his work. Much like black mold quietly spreading inside your walls, his insidious influence has seeped into every corner.

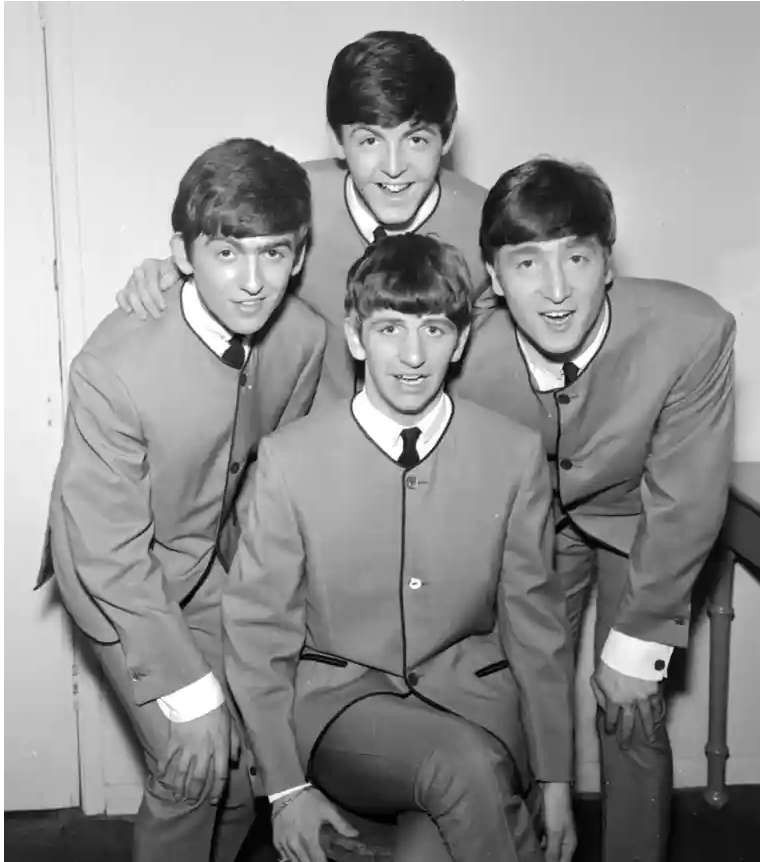

Cardin even left his bold mark on Beatlemania. The Fab Four, known for their stylish appearances, ended up looking more like valet drivers or busboys in their collarless and comical “George Jetson” suit jackets, all thanks to Mr. Cardin.

Pierre Cardin once uttered, “Fashion is not enough. I don’t want to be just a designer.” Regrettably for us, he indeed became more than just a designer…

[…] he was also a licensing pioneer, a merchant to the general public with his name on a cornucopia of products, none too exalted or too humble to escape his avid eye.

There were bubble dresses and aviator jumpsuits, fragrances and automobiles, ashtrays and even pickle jars. Planting his flag on the Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré in Paris, he proceeded to turn the country’s fashion establishment on its head, reproducing fashions for mass, ready-to-wear consumption and dealing a blow to the elitism that had governed the Parisian couture.

In a career of more than three-quarters of a century, Mr. Cardin remained a futurist. “He had this wonderful embrace of technology and was in love with the notion of progress,” said Andrew Bolton, the head curator at the Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

As the space age dawned, Mr. Cardin dressed men, and women, in spacesuits. In 1969, NASA commissioned him to create an interpretation of a spacesuit, a signal inspiration in his later work. “The dresses I prefer,” he said at the time, “are those I invent for a life that does not yet exist.”

His designs were influenced by geometric shapes, often rendered in fabrics like silver foil, paper and brightly colored vinyl. The materials would shape the dominant aesthetic of the early 1960s. It was a new silhouette that “denied the body’s natural contours and somehow seemed asexual,” Mr. Bolton said.

And speaking of the New York Times, back in 1985, Cardin said this about his design aesthetic: “I’m always inspired by something outside, not by the body itself. Clothing is meant to give the body its shape, the way a glass gives shape to the water poured into it.” The irony lies in the fact that Cardin, a clothing designer, held a deep disdain for the human body. To him, people were mere canvases to showcase his vision of futurism and modernity through his outlandishly clownish designs. It’s akin to an architect who views the baroque design of Versailles with contempt and disgust but somehow finds beauty in this monstrosity:

The truth is, it would be challenging to find a man more arrogant, boastful, and narcissistic than Pierre Cardin. He often touted his “talent” as a rare gift possessed exclusively by him. However, Cardin’s penchant for self-promotion and romanticizing his supposed “genius” served as a brilliant marketing strategy. Over time, Cardin managed to persuade the entire fashion industry into believing he was a space-age fashion deity sent to enlighten the masses. This was genuinely his distorted mindset. Cardin sincerely believed that he alone possessed “true taste” and that his version of “style” represented the epitome of the only real beauty. Cardin’s vision of modernity hinged on the idea that he not only had an innate sense of what was tasteful but also knew how to manufacture and sell it to the plebeians, who, in his view, lacked taste themselves. When it comes to “space age,” his arrogance was truly out of this world. However, it was in the 1960s that Pierre Cardin began leaving his indelible mark on society. The 1960s brought forth a profound cultural revolution that disrupted societal norms, and this atmosphere aligned perfectly with Pierre’s goal of eradicating traditionalism once and for all. Pierre’s brand of chaotic and unattractive fashion seemed to drain the beauty out of everything it touched. Furthermore, Cardin became an obsessive merchandiser, with his logo adorning everything from dresses and trousers to pickle jars and ashtrays.

Certainly, Pierre possessed remarkable business acumen, but his design talents left much to be desired. Moreover, he continued nurturing a profound aversion to anything old, traditional, or deeply rooted in history.

His “space-age” fashions also reflected a futuristic look with no link to the past, which he detested. Thus, he said: “The clothes I prefer are those I have created for a life that does not yet exist, the world of tomorrow.”

He later designed spacesuits for NASA and influenced the Star Trek uniforms in the television series.

His disdain for tradition is reflected in his “Bubble House” near Cannes. The massive building of geometric shapes contained ten bedrooms decorated by avant-garde artists.

Pierre’s bubble house stands as a stark example of geometric design that many find hideous and devoid of aesthetic appeal. His affinity for geometric shapes was closely tied to his obsession with genderless fashion, as he aimed to blend the distinctions between men and women into a single “unisex humanoid.” However, this vision contradicted the natural uniqueness and individuality that are inherent in fashion. The true beauty of fashion lies in how it enhances and complements the grace and form of the human body it adorns. This individuality is what makes the same garment look and feel distinctively different on each person who wears it. There is a divine and magical quality in the heart of fashion, something that Pierre Cardin vehemently opposed. In reality, his collectivist dogma clashed with the individualism of fashion. His designs concealed the natural beauty of women’s bodies beneath layers of geometric fabric, rendering them almost unrecognizable. His creations were more about him and his distorted vision of a dystopian future.

Looking at his designs, one can’t help but wonder if Pierre was indeed trolling women with these outlandish and grotesque outfits.

To carry out his revolution in fashion, Cardin enjoyed the patronage and support of the highest levels of the Establishment that he sought to destroy. He carefully selected those who could attend his shows yet introduced ready-to-wear clothing of his design for the masses. He was among the first to display his logo on his clothes.

He later developed licensing agreements with industries, which put his brand name on an enormous number of consumer goods, including cosmetics, pens, baseball caps, kitchen appliances, and even cigarettes. He once said that he would put his name on a roll of toilet paper if given the opportunity. The practice cheapened his brand but filled his pocketbook.

He would be commissioned to design uniforms and other clothes for governments, airlines, and other companies. He designed suits without lapels for the Beatles. American Motors Corporation (AMC) contracted him in 1972 to create the interior of its Javelin model, which used daring and outlandish fabrics and wild patterns.

All these practices tended to destroy fashion and contributed to the rise of bizarre shapes and patterns that characterize today’s runways.

Cardin was not jut some immoral byproduct of the sexual revolution. He was the godfather of his own anti-wholesome crusade and his lifestyle illuminated all the perversions, confusion, and chaos of that era.

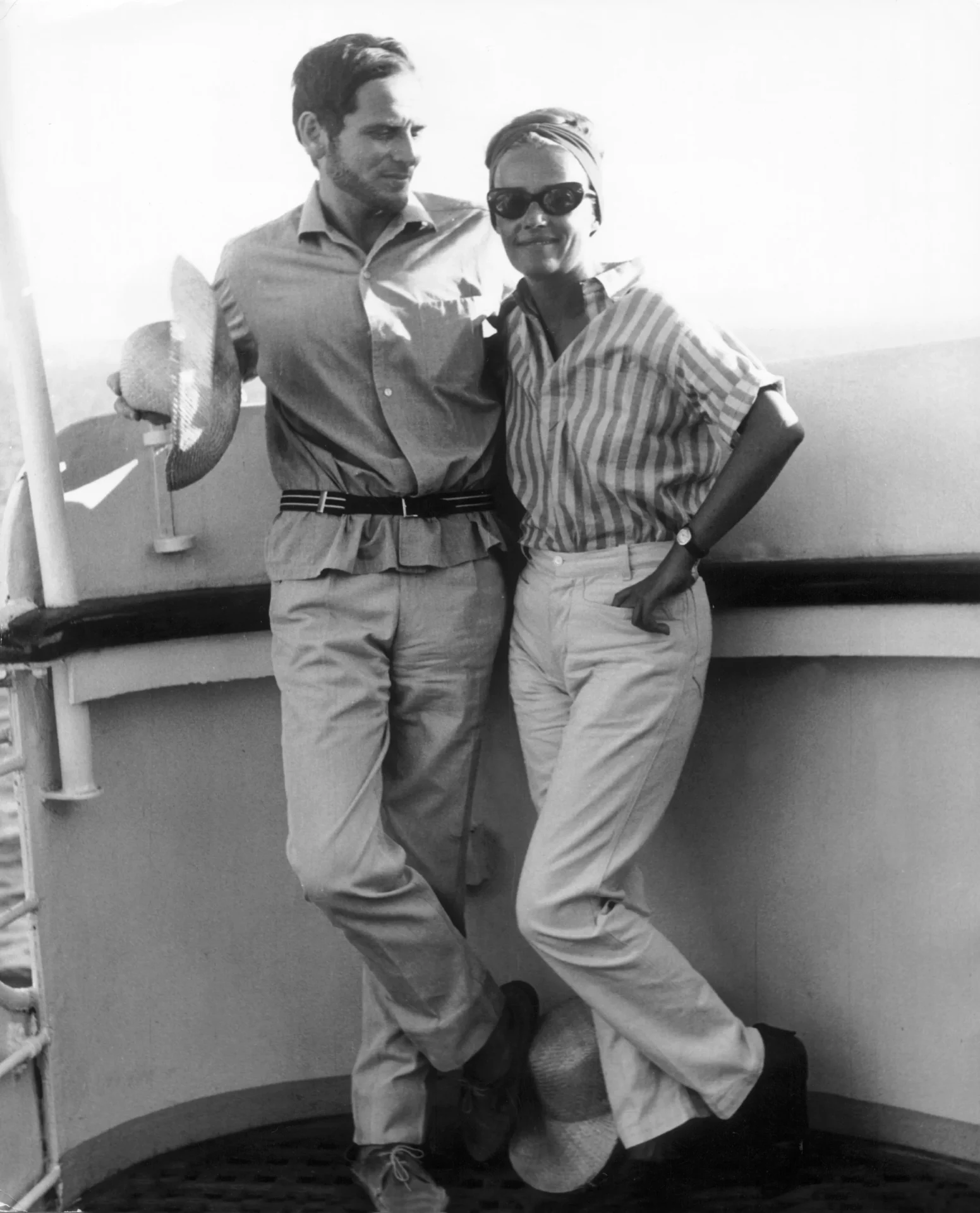

The word “confusion” aptly describes the essence of Cardin’s approach. Some argue that Pierre Cardin had an aversion to women, both in a sexual and general sense. This could explain his tendency to obscure the female form, transforming it into an otherworldly entity while simultaneously portraying the male physique as more feminine and alluring. In this context, there’s little need for the insights of Sigmund Freud. However, in 1961, Cardin crossed paths with the French actress Jeanne Moreau and claimed to have fallen in love. It is perhaps more accurate to view her as an exceptionally influential muse in his creative endeavors. Cardin was famously quoted as saying, “I didn’t like women, and I loved Jeanne.”

Pierre Cardin and Jeanne Moreau shared a relationship for four years. Following their breakup, Cardin returned to his homosexual roots and entered into a serious relationship with French fashion designer André Oliver.

Pierre Cardin’s purchase of an ancient castle, which once belonged to the Marquis de Sade, might seem ironic at first. However, the nature of the castle and its history shed light on the choice. The Marquis de Sade was infamous for his perversion and violence, with “sadism” being named after him. Some leftist fashion magazines have attempted to paint the Marquis de Sade as a complex historical figure with a sympathetic side, glossing over his dark deeds. This castle situation bears a resemblance to Jeffrey Epstein’s island, as both entail men with troubling pasts. Pierre Cardin used this castle, steeped in perverted and depraved history, to host avant-garde music and dance parties, reminiscent of the kinds of gatherings that would have occurred on Epstein’s Island. Cardin’s legacy in today’s world, marked by ugliness, gender manipulation, perversion, and mental illness, can be attributed to his role in promoting chaos, confusion, and depravity. His vision of a perfect future involved a world without rules, without a connection to our past, and a cold, unisex existence dominated by geometric shapes devoid of beauty or spirituality.

Unfortunately, Pierre Cardin’s idea of a twisted modern utopia continues to influence our lives today, three years after his passing.

SUPPORT REVOLVER — DONATE — SUBSCRIBE — NEWSFEED — GAB — GETTR — TRUTH SOCIAL — TWITTER

Join the Discussion