We need your help! Join our growing army and click here to subscribe to ad-free Revolver. Or give a one-time or recurring donation during this critical time.

On those bleak corners of the Internet that fret about economic growth, social cohesion, and other boring stuff, there’s a common question: What the heck happened in 1971?

On one chart after another for the United States, there is a pattern of steady growth and improvement in life that suddenly goes haywire right around 1971. Wage growth stagnated for all but the richest Americans. Inequality explodes. Housing prices began a long upward march that has yet to level out. Fertility rates crashed while illegitimacy surged. And so on, and so on.

Many other nations have data that tells a similar story, around a similar time. But one nation has a very different year that marks a shift in fortunes. In South Africa, the question could well be, “What the heck happened in 1994?”

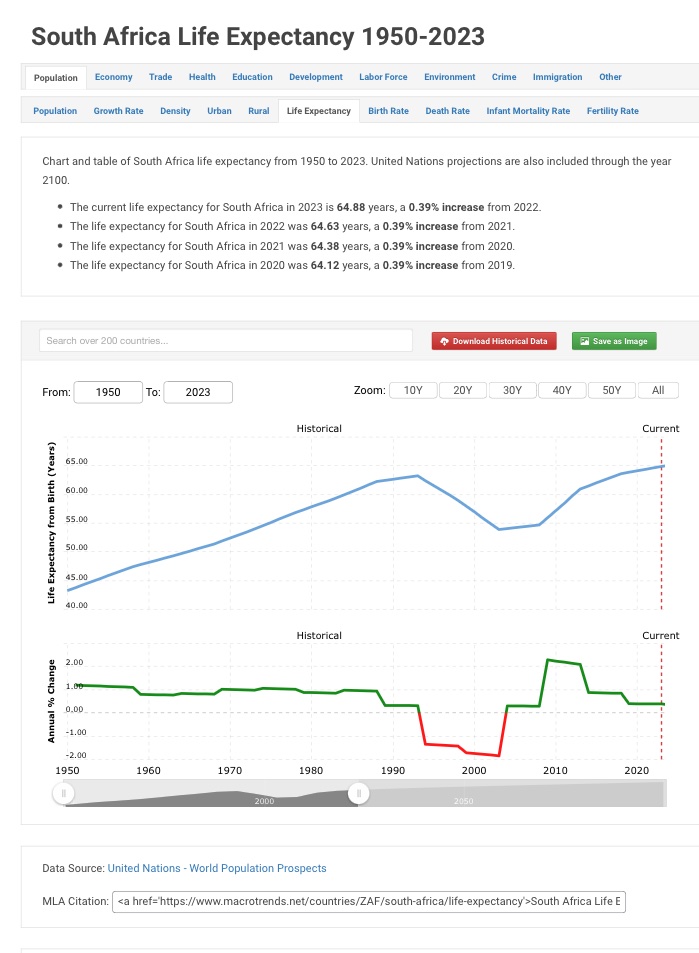

In that country, life expectancies grew until the early 1990s, when they suddenly went into reverse, driven heavily by an explosion of AIDS.

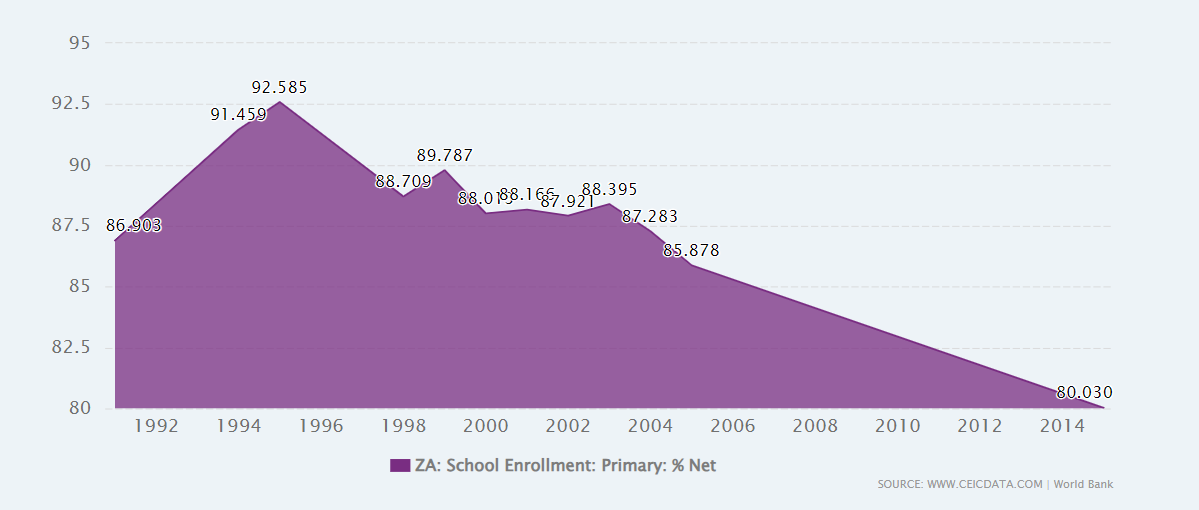

Primary school enrollment in the country peaked in the early 1990s but then started to go down, reaching only the low 80s by the mid-2010s.

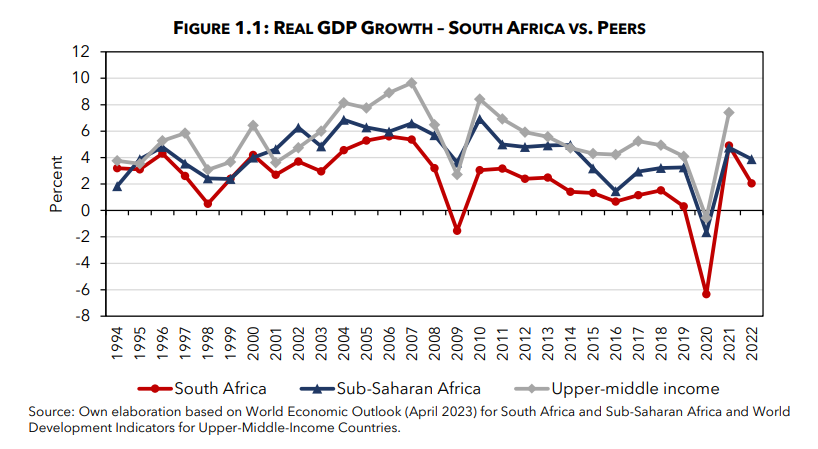

The last year that South Africa outperformed the rest of Sub-Saharan Africa in economic growth was 1994.

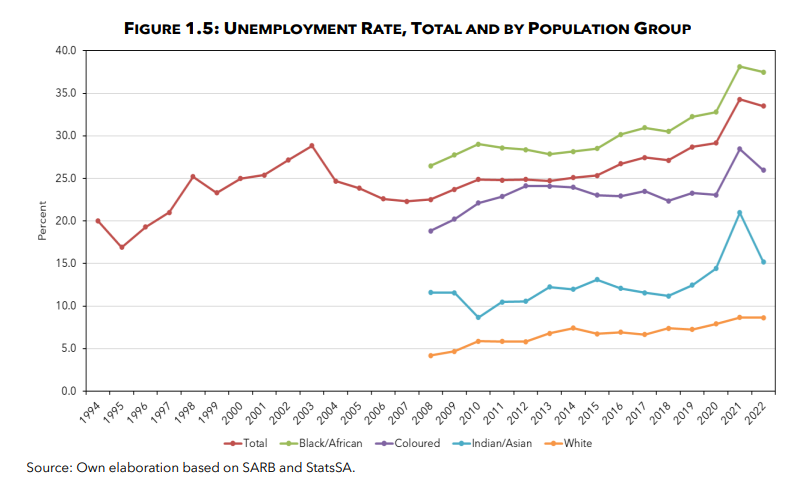

From 1997 onward, South Africa has never come close to matching the (already high) unemployment rate it had in 1994.

Man, what the heck happened to South Africa in the early 90s?

Not too long ago, South Africa was a darling of the global neoliberal order. The nation hosted a soccer World Cup (where its fans ruined things with the abominable vuvuzela). It had that schmaltzy feel-good movie with Matt Damon and Morgan Freeman. The BRIC countries of Brazil, Russia, India, and China gave South Africa a sympathy invite to join the newly-renamed BRICS cabal. South Africa was the nation that would prove a post-colonial, post-European majoritarian multiracial democracy would astonish the world.

A new report from Harvard sums it up thusly:

The early 1990s marked a victory for generations of freedom fighters, and the future of an inclusive South Africa was set in motion. There was no telling what could be accomplished with the full force of South Africa’s human capabilities, creativity, and resilience in combination with its industrialized economy and established comparative advantages in global trade. […] The Rainbow Nation seemed poised to leverage its substantial economic assets at full strength. In 1995, South Africa supported the 47th most complex economy in the world — on par with China (ranked 46th) and far ahead of any other African nation (Tunisia was next at 66th). There was good reason to believe that the economy would grow rapidly, and opportunity would expand to many more South Africans.

Uh, yeah, about that.

You all know how well things went. But what’s incredible is that now even Harvard is giving up on the country.

Courtesy of the university’s “Growth Lab” at the Center for International Development, we have a lengthy 178-page paper titled “Growth Through Inclusion in South Africa.” But despite the title, the paper is actually about how the drive for “inclusion” has caused growth to disappear from the unfortunate country:

South Africa’s economy is stagnating and, in fact, losing capabilities, export diversity, and competitiveness. While the racial composition of wealth at the top has changed, wealth concentration in South Africa has not and remains very high. Moreover, the broader structures of the economy have not allowed for the inclusion of the labor and talents of South Africans — black, white, and otherwise.

The report is a gruesome, piece-by-piece dissection of South Africa’s failed economy, dressed up in just enough euphemisms to be publishable while allowing the more alert and informed to see the truth.

Income per capita has been falling for over a decade. Unemployment at over 33% is the world’s highest, and youth unemployment exceeds 60%. Poverty has risen to 55.5% based on the national poverty line, yet many more households depend on government transfers to sustain meager livelihoods.

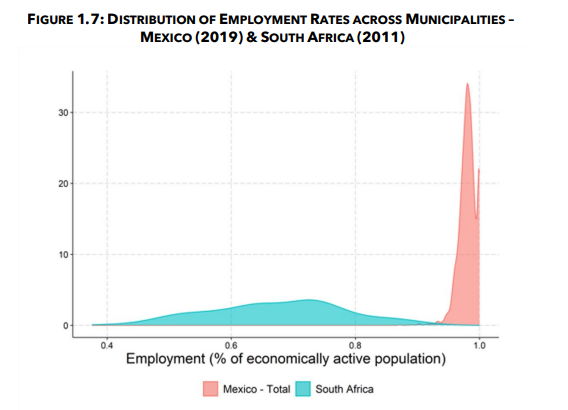

Things are so bad that South Africa is getting utterly, devastatingly clowned on by Mexico, of all countries.

Other countries falter because of bad business cycles, a glut of risky loans, too much debt, or a crash in a major industry. Yet, as Harvard notes, South Africa has a diverse economy, spanning mining, agriculture, and industry, yet its malaise spans more than a decade, a period when much of the rest of the world was booming.

So what’s to blame? Quite simply, an inability to actually govern:

South Africa is facing the economic consequences of collapsing state capacity. This is the predominant driver of South Africa’s weakening economic performance and is at the heart of intensifying macroeconomic stress. … South Africa needs a strategy to recover state capacity or else slowing growth and increasing exclusion will continue to worsen.

Falling “state capacity?” What could they possibly mean by that?

We identify four strongly interacting causes underlying such systematic collapse: gridlock in the ruling coalition that prevents action; an ideology that justifies excluding society from participating in state-reserved activities, over-burdening of public entities with goals beyond their core missions and capabilities, and political patronage that has corrupted both the state and the ruling coalition.

Don’t be fooled: Those are not four different reasons for South Africa’s government collapse. Rather, they are all the same reason. Every cause of South Africa’s collapse above is, in reality, just a manifestation of the ruling ANC’s reconstruction of the entire country along racial lines.

Now, the Harvard Growth Lab never quite says that in those words. Instead, like trained Straussians, they speak vaguely and let the reader (or us) fill in the blanks. For instance, the paper briefly mentions how state-owned electricity company Eskom has been disintegrating because it has most unfortunately “lost critical talent and technical expertise.” How sad! What happened? Did the talent get poached by the private sector? Did the talent die of Covid? No and no. South Africa deliberately purged its talent, paying them to leave the company because they were of the wrong race.

Eskom, which readily concedes it does not have the skills to maintain its plants, is on a drive to bring back former employees to mentor and train staff. … An accelerated loss of skills at Eskom has been underway over the past two decades when old employees were encouraged to take voluntary severance packages to bring in new black graduate engineers.

But while the new entrants often had superior qualifications, such as engineering degrees, compared to the artisans they replaced, they lacked the experience of their predecessors, many of whom had worked their entire lives at Eskom.

What is the “political patronage” that Harvard describes as so cancerous to the country’s fortunes? It’s not just generic corruption, but in fact a well-known component of the ANC’s entire political order: cadre deployment. The term comes straight from Joseph Stalin himself, who told a class of Red Army cadets that “cadres decide everything” in 1935. The Communist-aligned ANC (they are literally in a coalition with the Communist Party) has adopted the same concept, which calls for deploying party loyalists into every lever of government. From the very beginning, the justification for cadre deployment was a radical redistribution of jobs based on race. In 1998, the South African Mail and Guardian wrote it up this way:

In the document produced in the current issue of the ANC booklet, Umrabulo, the author says … “In these four years of democratic government, what have we done to train and deploy personnel in strategic areas within the state – positions in the security forces and the bureaucracy such as pilots, air controllers, immigration officials, finance management and information technology? … Transformation of the state entails, first and foremost, extending the power of the national liberation movement over all levers of power: the army, the police, the bureaucracy, intelligence structures, the judiciary, parastatals and agencies such as regulatory bodies, the public broadcaster, the central bank and so on.”

[…]

If accepted, the paper would spell an end of the so-called “sunset clauses” – a package of constitutional compromises proposed by former senior ANC negotiator, the late Joe Slovo.

[…]

The agreement included an ANC pledge to secure jobs for white civil servants for at least a period of five years.

So, does Harvard’s long report give any of this context? It does not. Instead, the report merely observes, “It is a long-standing policy of the ANC to place party members in influential roles across government and crucially parastatals,” and notes that South Africa would be far better with “merit-based” hiring for employees.

A similar sleight of hand takes place with another cause of the country’s disintegration, the policy of “preferential procurement.” It takes Harvard until page 74 of the report to even define what preferential procurement is, and it does so with the bland definition that it “[gives] preference to previously disadvantaged groups.” Of course, preferential procurement is exactly what it sounds like: giving government contracts to inferior options simply because the ownership is black or female. Just like in the U.S., this leads to ridiculous cases of corruption, inefficiency, and fronting, where black-owned companies simply buy products from a real company and provide them at a markup to the government while taking a cut.

Despite its dry definition, Harvard’s paper actually warns that preferential procurement is utterly destroying the country. These racially-allotted contracts raise government costs by 28% in agriculture, 27% in transportation, 28% in public works, 62% in sports and cultural spending, and so on. Overall, the paper argues that just getting rid of preferential procurement would save an annual amount equal to 3% of South Africa’s entire GDP. When the paper gets to general recommendations on raising South Africa’s state capacity, the very first proposal is to immediately ditch preferential procurement, with the second being to implement merit-based hiring for government employees.

In other words, Harvard’s top two pieces of advice for fixing South Africa are, “Get rid of race-based hiring, and get rid of race-based contracts.”

Two years ago, Revolver warned about South Africa’s coming fate as, in essence, the first nation ever built on the doctrines of Critical Race Theory. The words might be different—”black”economic empowerment,” “employment equity”—but the core concepts are identical. Authorities deem any economic or social metric according to which whites outperform other groups as evidence of “systemic racism,” which must be fixed with direct intervention. If the gaps prove surprisingly stubborn, more direct interventions are necessary. Preferences become quotas. Social welfare becomes wealth confiscation.

READ MORE: South Africa—The First Country Built on “Critical Race Theory”—Officially Implodes

Thirty years ago, Harvard and virtually every other institution on Earth celebrated as South Africa adopted this system. They were still celebrating it just a few years ago. In 2020, they publicly agitated for it to be expanded all across America. If asked publicly, they would probably still say they want South Africa’s system; look no further than Harvard’s hysterical wailing after last summer’s affirmative action court decision.

But this unity is crumbling. No doubt, virtually every one of the dozens of faculty, fellows, and students at Harvard’s “Growth Lab” are liberals. It’s possible that not a single one of them voted for Donald Trump. Some might have rocked a “In This House, We Believe…” sign outside their home in 2017 or a “Black Lives Matter” banner in 2020.

And yet, stark reality stares them in the face: South Africa embraced government-by-CRT and has been destroyed. If it wants any hope of turning its fortunes around, it must abandon that path. One wonders whether the authors of the piece would extend these basic principles to their own educational institution or whether Harvard would have to fail on the level of South Africa to allow such critical self-reflection. Indeed, one gets the cynical sense that this reluctant and highly euphemized reappraisal of South Africa’s anti-white racial policies is something of a desperate effort to salvage the Rainbow Nation’s reputation. After all, the nation hailed as the paragon of multiracial democracy devolving into a situation in which it can’t even manage reliable electricity is a remarkable embarrassment to the ruling ideology of the post-War West.

In the same way that Gavin Newsom could countenance a brief period of clean streets for San Francisco in honor of Chinese Premier Xi’s arrival, perhaps the dramatic extent of South Africa’s demise allowed for a rare bout of rational thinking about South Africa’s affirmative action regime—just enough to put the lights back on, perhaps. However temporary and compartmentalized these lessons might be for the Harvard researchers, they are plain as day for us, and yet they reveal another troubling glimpse at the dark future that awaits if we don’t course-correct radically and quickly.

SUPPORT REVOLVER — DONATE — SUBSCRIBE — NEWSFEED — GAB — GETTR — TRUTH SOCIAL — TWITTER

Join the Discussion