We need your help! Join our growing army and click here to subscribe to ad-free Revolver. Or give a one-time or a recurring donation during this critical time.

Guest Post by Jeremy Carl

I was in the middle of responding to my publisher’s edits of my forthcoming book when this site’s proprietor, having seen a few of my tweets on Buffett’s passing, reached out to me and asked me to do a reminiscence.

Reader, I did not have time to write it. It was definitely not wise to distract myself from my “real work” by writing it. But it would be *fun* to write—and Jimmy Buffett would have never missed an opportunity to do something more fun. So I wrote it.

They say to never meet your heroes, but I almost ended up working for one of mine.

Back in the 1990s I was working in the tech business for a technology and media company that at the time had acquired an outsize level of importance in the still embryonic digital music landscape. Jimmy Buffett, who was early to see that the Internet presented a huge business opportunity, had reached out to us through a representative to talk about the possibility of a joint business venture.

I was a huge fan, and so I found myself flying down to southern California to see a Buffett show, where I had a backstage pass (it was amusing to see the rock star life from the other side of the curtain.) Afterwards, I went to meet with Buffett for what was supposed to be a half hour to discuss business at the bar at his hotel (The Ritz Carlton Laguna Niguel—Jimmy was far beyond his crash pad days back then.).

Well, a half-hour ended up turning into about five hours over drinks. We talked a bit of business, and Buffett could tell that I was a fan of and knowledgeable about his music, but we spent more time than anything else, talking about a shared taste in literature from Mark Twain to Ernest Hemingway. I’ve been fortunate to have had a lifetime of adventures and to have met many famous people, but few of my experiences could ever top that evening.

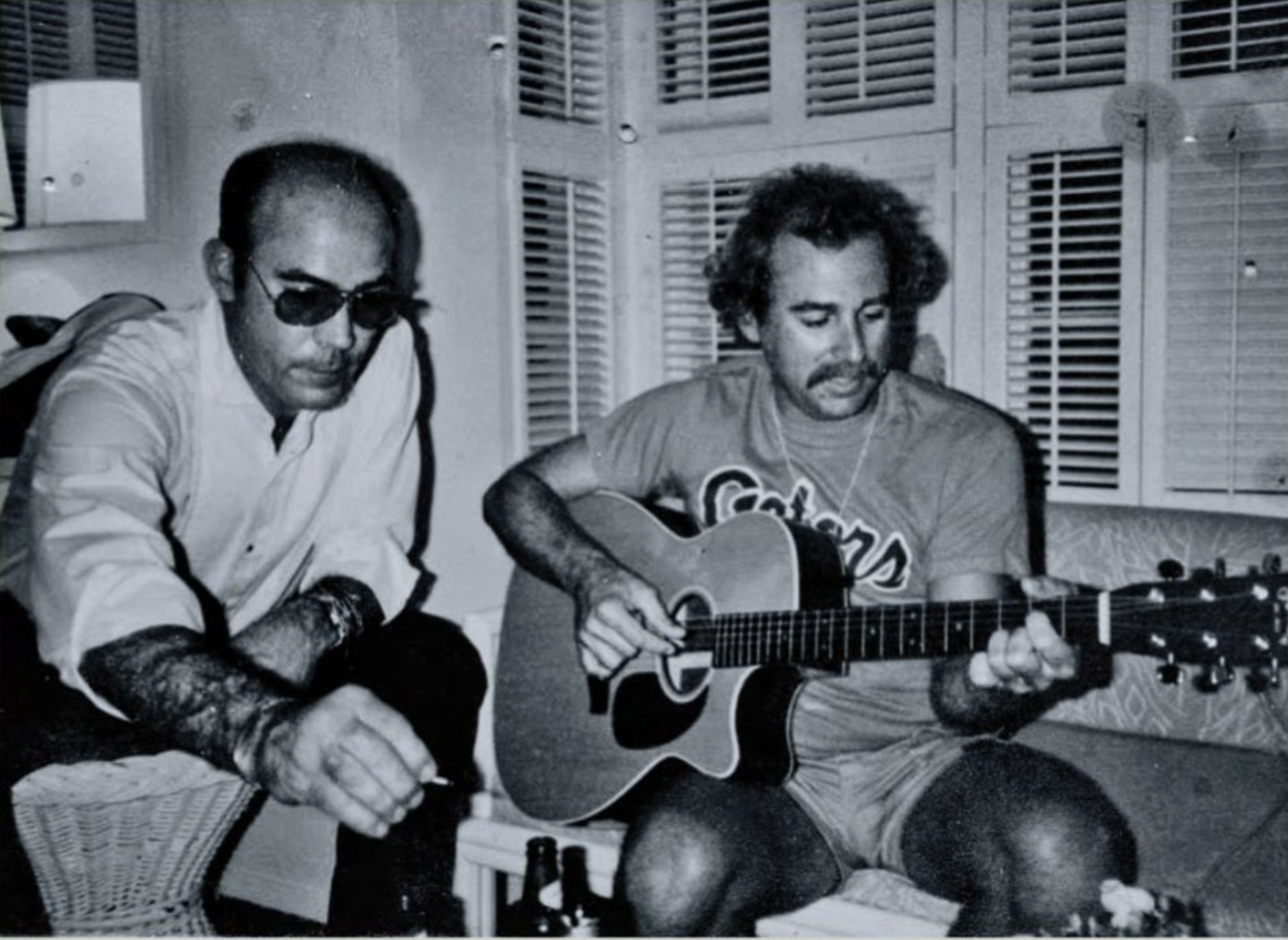

Buffett, who in addition to his musical career was one of only a few people ever to have a #1 NY Times bestseller in both fiction and non-fiction, always had always loved good writing. In his Key West days, he had hung out with a literary crowd that included great American writers like Richard Brautigan and Jim Harrison. He was especially close with Tom McGuane, another soon-to-be distinguished American writer, who later married Buffett’s sister.

A few days after our meeting, I got a call from one of the leaders of Buffett’s business team. After a bit of small talk. He told me that Jimmy wanted me to help grow the digital side of his burgeoning Margaritaville empire. I was surprised by the offer, and flattered of course. And I thought sincerely about doing it but ultimately didn’t. There were a variety of lame practical reasons of course, but the real reason was that I just couldn’t imagine having a business relationship with somebody who’d I’d admired for so long as a fan. I’d shared a magical night of conversation with him, and he was just as I’d imagined and hoped—warm, witty, intelligent, full of great stories and fun. That was how I always wanted to think of him—not as my boss!

I’d first become a big fan of Buffett’s while a student at Yale, largely as an antidote to the university’s achieve-at-all costs ethos. Jimmy was relaxed, friendly, and made it seem like nothing had big stakes, and there would always be oysters and beer at the end of the rainbow.

Barstool Sports’ Dave Portnoy captured this mood perfectly, in a posthumous tribute, saying that “Another huge reason he meant so much to me is that I’ve always vacillated in my life between whether I wanted to chase money and work my ass off or whether I should just f-ck off and disappear somewhere.” Buffett managed to embrace the fun-loving lifestyle that allowed him to become an icon of the relaxed, island life while simultaneously working hard enough—and smart enough—to become a self-made billionaire.

When Buffett’s death was announced, most of the tributes were what I would have expected but I was surprised by how many people who had a far more extended relationship than I did with Buffett had the same type of special experience with him that I did that night. It seemed that unlike many artists, the private Buffett and the public Buffett were very similar people. Arena rock legend Bob Seger tweeted out that he was “Sunshine personified. I never met a human being that didn’t like him.” It was a sentiment echoed by several others, including Paul McCartney who gave him a long, touching tribute on X/Twitter.

The media and critics never really loved him—one suspects because he was wildly successful and shamelessly commercial in an unabashedly American way. With a world-spanning business empire, Buffett defied the “tortured, starving artist” stereotype that journalists and critics looked for.

Actual artists knew better; McCartney wasn’t Jimmy’s only prominent fan. Bob Dylan, James Taylor and many other highly acclaimed singer-songwriters, who, dare we say, knew a bit more about good music than the average critic, were all Buffett aficionados.

And indeed, if you listen to his early albums like A1A, White Sport Coat and a Pink Crustacean, Havana Daydreamin’, and Livin’ and Dyin’ in 3/4 Time that chronicle Buffett’s early Key West adventures and some even before, you’ll hear some of the best popular songwriting America has to offer, sometimes done with sly humor, but just as often with a gorgeous wistfulness that belied his relative youth. “You Had to Be There”, Buffett’s impishly titled 1978 live album, recorded during his creative heyday and just as “Margaritaville” was taking off, captures the wild energy, creativity, and fun of those early days.

Indeed, Buffett’s career arc offered somewhat of a philosophical and artistic conundrum. After “Margaritaville” brought him lasting fame, he became the person/persona known today by most casual listeners who wouldn’t know the difference between “Tin Cup Chalice” and “Nautical Wheelers”. He made tons of money and delighted millions of fans, but his artistic output (in the opinion of many old school fans) only rarely touched the high points of his first several albums, and he sometimes produced work that was far beneath his considerable talents.

But he made so many people happy, had a great life, and reached a wider audience than ever.

So what’s the purpose of art?

Would Buffett have been better off as a moderately commercially successful singer-songwriter writing great material in semi-obscurity?

Would the world have been better off if he had done that?

It’s hard to say, but at the end of the day, I’d have to say no—Buffett’s songs—the great ones, and even the not-as-great-ones, gave a tremendous amount of joy to everyday Americans who would flock to his concerts that they would turn into traveling parties where everyday folks could forget their troubles and relax and enjoy an endless summer weekend wherever they were.

And indeed, thanks in no small part to Buffett’s inspiration, I did something even better than having a job with Jimmy Buffett. For a while, I lived something even slightly resembling a Jimmy Buffett lifestyle (albeit with far fewer intoxicants). Like a character in one of his songs, in my late 20s, I quit my “responsible job” in tech and traveled the world for two years, having numerous adventures along the way, before finally living the other half of a Buffett fan lifecycle–settling down, getting married and having five kids (whom we eventually took around the world for a year, hopefully whetting their own appetites for fun and adventure).

Without Buffett’s inspiration I would have never done that. Indeed I suspect it’s not entirely coincidental that when I finally “settled down” I did so in a part of Montana that Buffett frequented, and sang about, in his early days as an artist.

There are many people in the political and policy world who have had more “distinguished” careers than I have. But there are very, very, very few, who have had more adventure and more fun. And I have to thank Jimmy for that.

A friend of mine texted me shortly after Jimmy died about what would have happened if I’d taken that job with him—I certainly could have avoided a whole lot of trouble and hate-mail! But I wouldn’t change anything.

Jimmy’s life personified for me the words of the legendary outdoorsman “Nessmuk,” who, toward the end of his life, remarked: “Tempus Fugit [time flies]—Let him fly, let him flicker—I have been there and done it.”

Thanks so much for all of the great times, Jimmy. Fair winds and following seas.

Jeremy Carl (@jeremycarl4) is a senior fellow at the Claremont Institute.

SUPPORT REVOLVER — DONATE — SUBSCRIBE — NEWSFEED — GAB — GETTR — TRUTH SOCIAL — TWITTER

Join the Discussion